Arissana Pataxó

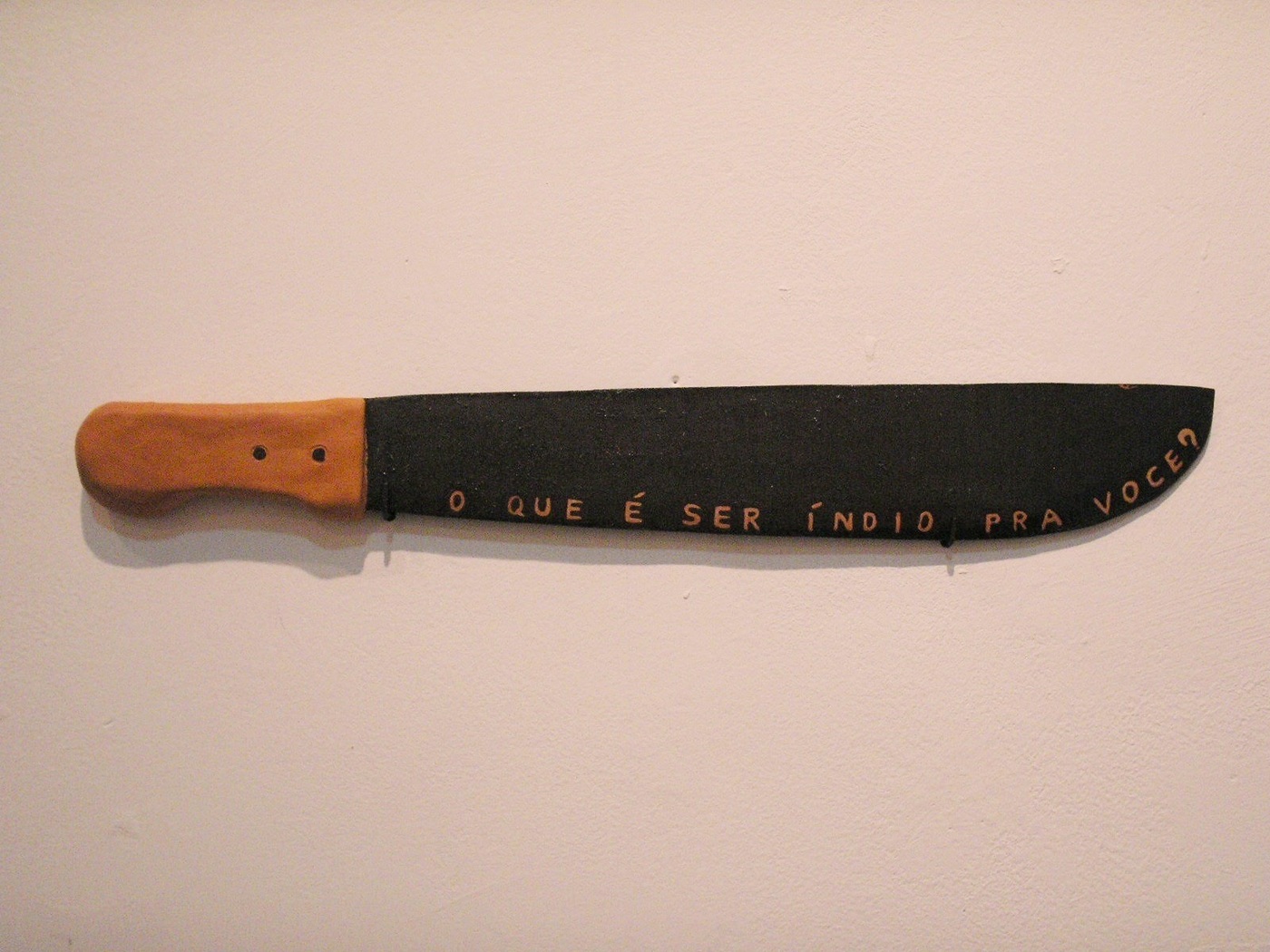

Arissana Pataxó’s 2009 sculpture Mikay (“cutting stone” in the Patxôhã language), consists of a ceramic machete, which poses the question “What does being an Indian mean to you?” [“O que é ser índio pra você?”] and challenges the stereotypes projected onto Indigenous peoples in Brazil that are reinforced by literature, the media and the education system.

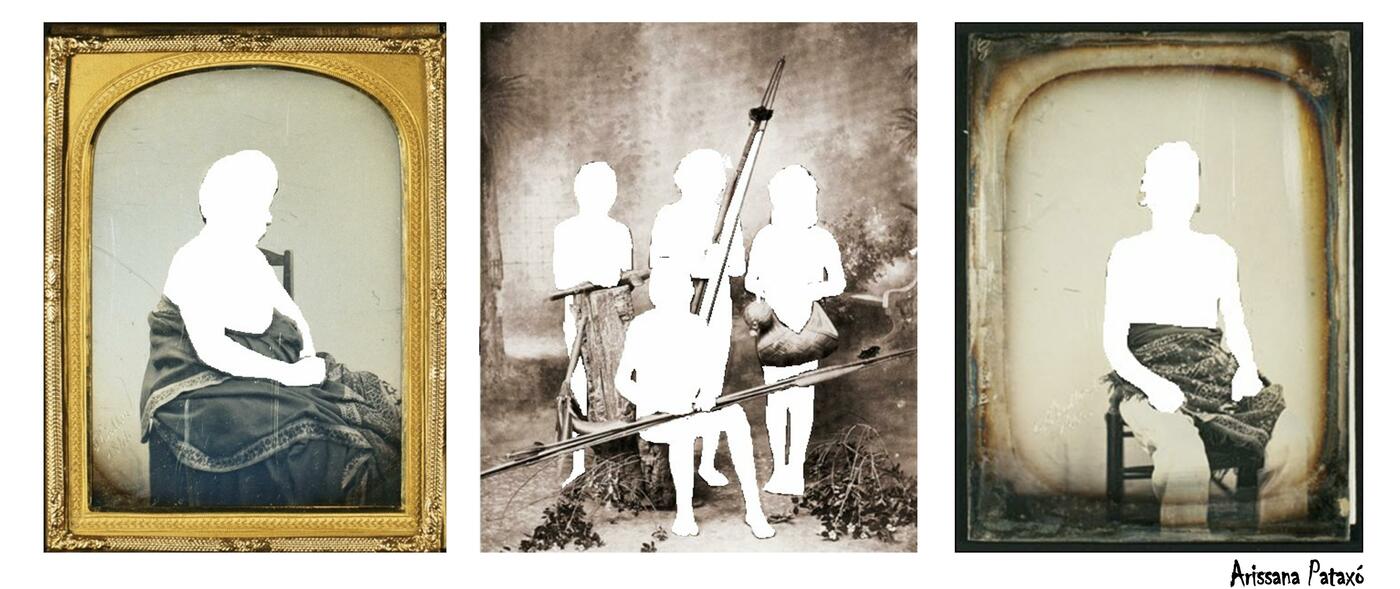

Micay is followed by the 2020 tryptic Indigente, indi(o)gente, indigen(a)-te, which engages with the blanking out of Indigenous identity. Arissana Pataxó's interventions in this series of 19th-century black-and-white portraits can be read as a comment on the forced erasure and invisibilisation of indigeneity in Brazil’s colonial and recent history.

By removing their faces from the portraits, Pataxó makes the violence explicit: these are portraits without faces, without markers, without identity. The title of the tryptic plays with the etymologically false connection between the words “indigent” and “Indigenous”.

In Brazilian Portuguese, the word “indigente” not only means pauper or destitute, as it does in Latin, but is also a legal and journalistic term used to describe unidentified dead bodies, particularly in the expression “enterrado como indigente” (buried as someone with no identity and no relatives). Pataxó’s intervention equates the lost identity of the photographed subjects to the lack of identity of destitute dead bodies that are buried without a name, without relatives or friends.

By linking the words “indigente” and “indígena”, she also interpellates the racist de-humanisation of Indigenous individuals by Western knowledge practices, a fact that becomes even more explicit with the poetic transformation of the word “indigente” into “indio(é)gente” (indian is human).