Ashanti Dinah

Ashanti Dinah was born in Barranquilla (on the Caribbean coast of Colombia) and is an Afro-Colombian activist, poet and teacher. Her research has focused on analysing how some literary works by Afro-Latin American writers challenge the institutional and monological code of imperial language and respond to racism and other forms of oppression by deploying a kind of aesthetic maroonage.

Ashanti Dinah's training has been in languages and literature and in 2021 she started as a doctoral candidate at Harvard University. She has published a collection of poems, Las semillas del Muntú (The seeds of Muntú, 2019) and has another unpublished one, Alfabeto de una mujer raíz (Alphabet of a root woman). Her poems have been translated into Portuguese, English and Bulgarian, and have won several awards, including the Benkos Biohó Award (Bogotá, 2016).

Ashanti Dinah's collaboration with CARLA consists of a long contribution to the project blog and participation in online events on art, anti-racism and affection. For this exhibition, she worked with CARLA researcher Carlos Correa and Afro-Colombian artist Wilson Borja to produce illustrations and animations of three of her poems from Las semillas del Muntú. The poems (reproduced in English translation below) and illustrations touch on Afro spirituality and ancestry, affirming Afro epistemologies in the context of anti-racist literature and struggles.

My Ancestress

For centuries she has been setting fire to

the mossy padlock of my body.

Her heritage adorned with seashells

is a premonition in my veins.

Our lives interweave

beneath the sacred ceiba tree.

Those who knew her,

remember her rocking herself in her wicker rocking-chair

Serene, as if not haunted by the dizziness of death

facing the dawn.

They say that cats hunted the twilights

in her hands.

They say that rusty ships appeared

at the pier of her eyes.

They saw how the south wind

carved her a mantra of Olokun.

They still see her running

among the crevices of the kingdom of this world

with a fragment of daybreak between her lips.

In the doorway of the old courtyard of my childhood,

they have seen her become a strange creature

pecking amongst the chickens.

The life of the dead

Yesterday, a Nganga priest said to me:

the dead are born from the four seasons

with the enigma that is life.

They never die: they just melt the murmur of their breath into the

Earth.

When they reincarnate they are liquid mirrors of

ourselves:

We can feel the patakí of their lives.

When they work in the heart of the jungle

they become a weave of nests, arms of moss and mangrove

on a sea of beginnings.

Their faces are carved into our hands

covered in mud, clay and uproar.

When they wander, they become inhabitants

of the stars, passengers of the air.

That is their way of staying alive

in the song of a bird.

They come from the past to contemplate us.

Like a chorus of bees they furrow the curve of the retina.

A lunar mystery orbiting in their gaze

deciphers our thoughts.

They are the invisible narrators of our dreams.

They whisper among themselves of images

that become ideas and words.

They trace out channels on our bodies,

forests of nostalgia, resonant fragments

where the weight of our memories can lie.

They are the rain setting the rhythm of the days.

If we listen to them we feel percussion

galloping across the hills of our tongue.

The artillery of a force in the core of our soul.

We make offers to them of fruits and flowers.

From them comes the freshly baked bread,

the afternoon coffee, the sweet drink at day’s end.

Syllable by syllable, they are invoked with the balm of prayer.

They are serenaded with the blood of our animals,

bonfire of verses that lights up their absence.

We spray rum from our mouths and they prophesy to us

with words liberated from the stocks and the whip.

Let the voice of the dead fall at our feet!

Let our fingers feel the drum of their tempest!

Let them dance with us to the tune of the most

ancient melody!

A Tribute to My Great-Great-Grandmother

moforibale

I greet you grandmother of my grandmother,

with the name of a jungle or the musical name of a river.

Iron brand on the slave barracks of my shoulders.

Motherland of the night,

accomplice of the stars,

from your curly hair hang constellations of feathers.

I see myself reflected in your eyes of a bird-woman

turned into a rustling of leaves.

I give you this prayer of a witch’s creed

with my forest tongue.

My healer, when I pronounce your name

my mouth overflows with tenderness.

You appear here at the balcony of my memories,

on the calligraphy of my heart.

Proclamation of my enslaved African blood,

I caress the spirit of your womb:

that terrace with aromas of lemon balm and sage,

of rosemary and bay

with hints of cassava and molasses.

I offer you my song so you can run free

and smooth away the wrinkles of your sadness.

I give you thanks for accompanying me on my way

and spreading sunlight on my roots.

I greet you, midwife of hopes,

clairvoyant

tobacco smoker.

At my dawn reawakening, let

eucalyptus and cinnamon spring up alongside your fronds.

I ask you, be the guide for the map of my life.

Today I dedicate to you my finest proclamations

These poems tap into the ancestral past, evoking the presence of generations of the dead in the texture of our dreams and bodies, in the skies and in the soil, in what we eat and the rhythms of our movements. The ancestors here are linked firmly to Africa and the African diaspora with references to a Nganga priest, moforibale (a greeting to African deities), patakí (an Afro-Cuban religious story) and Olokun (a Yoruba goddess); and with the mention of enslavement and of language liberated from the stocks and the whip.

A sense of the rhizomic networks and movements of the diaspora is conveyed by images of nests, mosses and mangroves, constellations of feathers, fronds, crevices, fragments, rustling of leaves and cats hunting crepuscular glintings that dance in the hands of an ancestress.

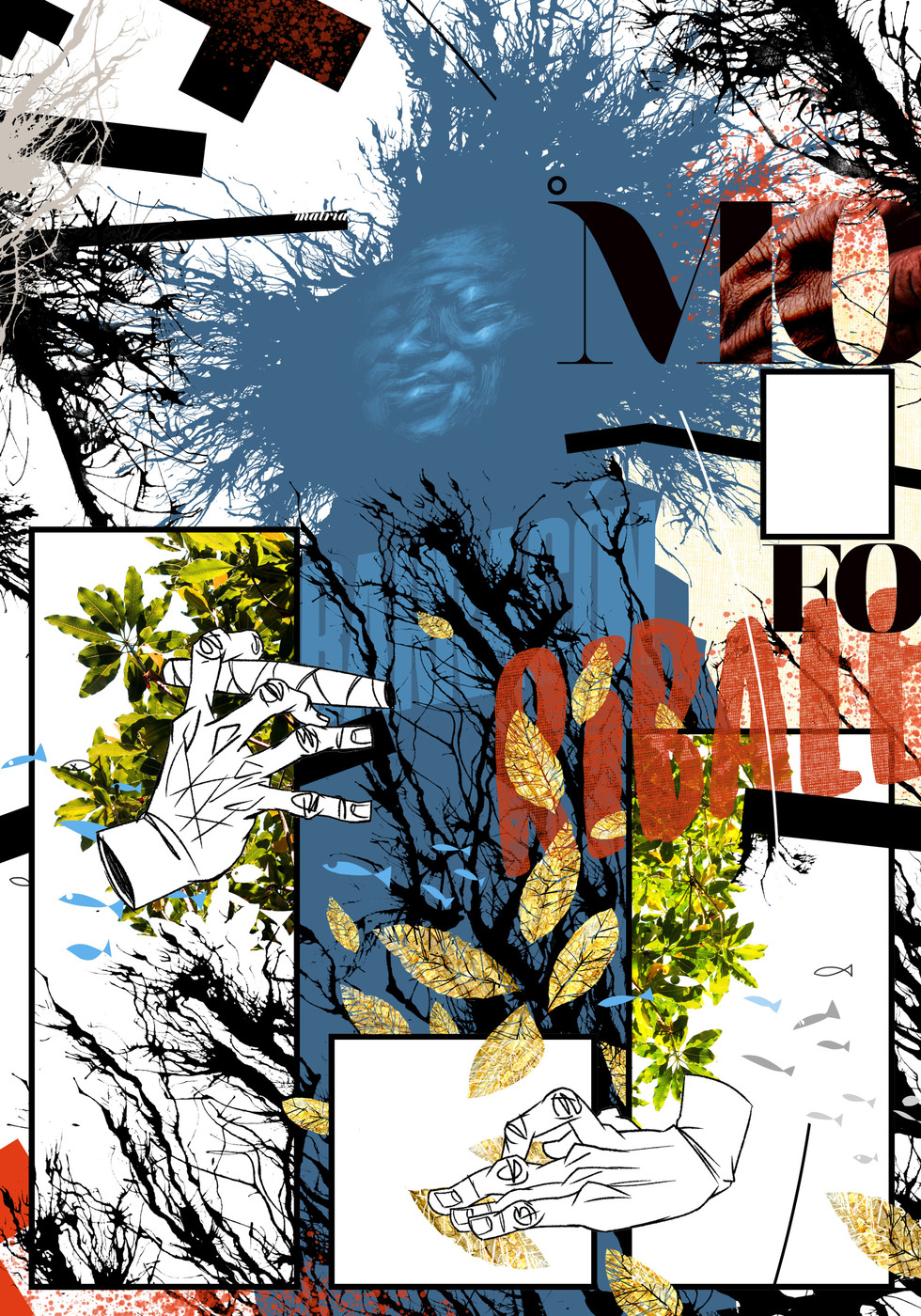

The illustrations by Wilson Borja dramatise the tension between ancestry and diaspora that is evident in the poems. On the one hand, ancestral roots are symbolised in the ceiba tree, the racialised human body - hands, hand prints, a face, a female form - and the Afro-Cuban religious symbols (circles and crosses). On the other hand, endlessly diasporic proliferation is conveyed in images of multiplying fronds, intermeshed with exploding Afro hair, fishes in motion, visual fragmentation and disjuncture.

The poems and the illustrations together form a powerful affirmation of African diasporic spirituality and ancestral connection, alongside a celebration of the endless disjunctures and multiplications that mark the African experience in the Americas.