Argentina

Argentina has long prided itself on having a population that “came from the boats'' - the ones that brought almost 6 million European immigrants to the country in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in search of land and economic opportunity. Around the same time, vast tracts of land were annexed by the devastating Conquest of the Desert, a military campaign that decimated the still autonomous Indigenous nations in Patagonia and the Chaco region, driving the people off their territories, often into urban areas.

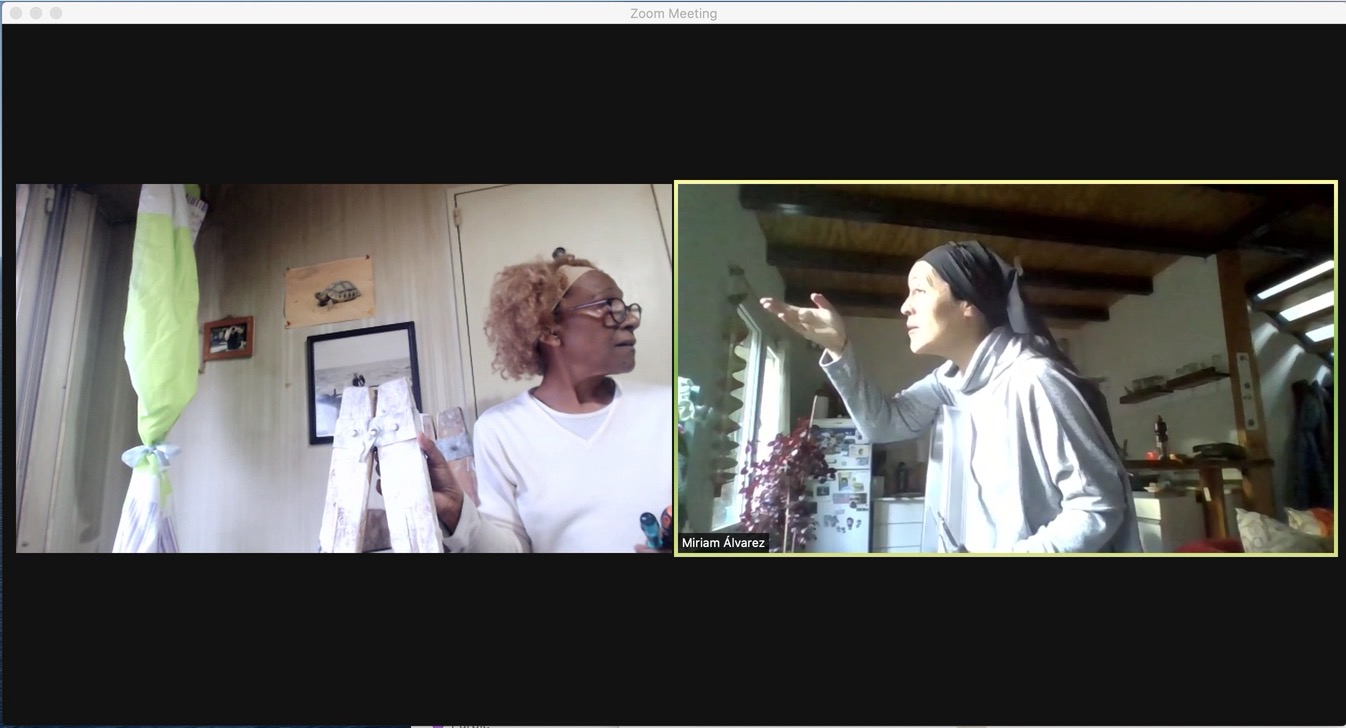

The presence of Black people, who in the early nineteenth century were about 25% of the population of Buenos Aires (and over 50% in some agricultural regions) gradually declined, as Afro community organisations were called upon by the elites to contribute to national integration through de-ethnicisation and state institutions stopped recording ethnicity and race. Afro-Argentines became invisible in statistics and in the public imagination, as the image of Argentina as a primarily white/European nation grew and gradually became dominant at the beginning of the twentieth century.

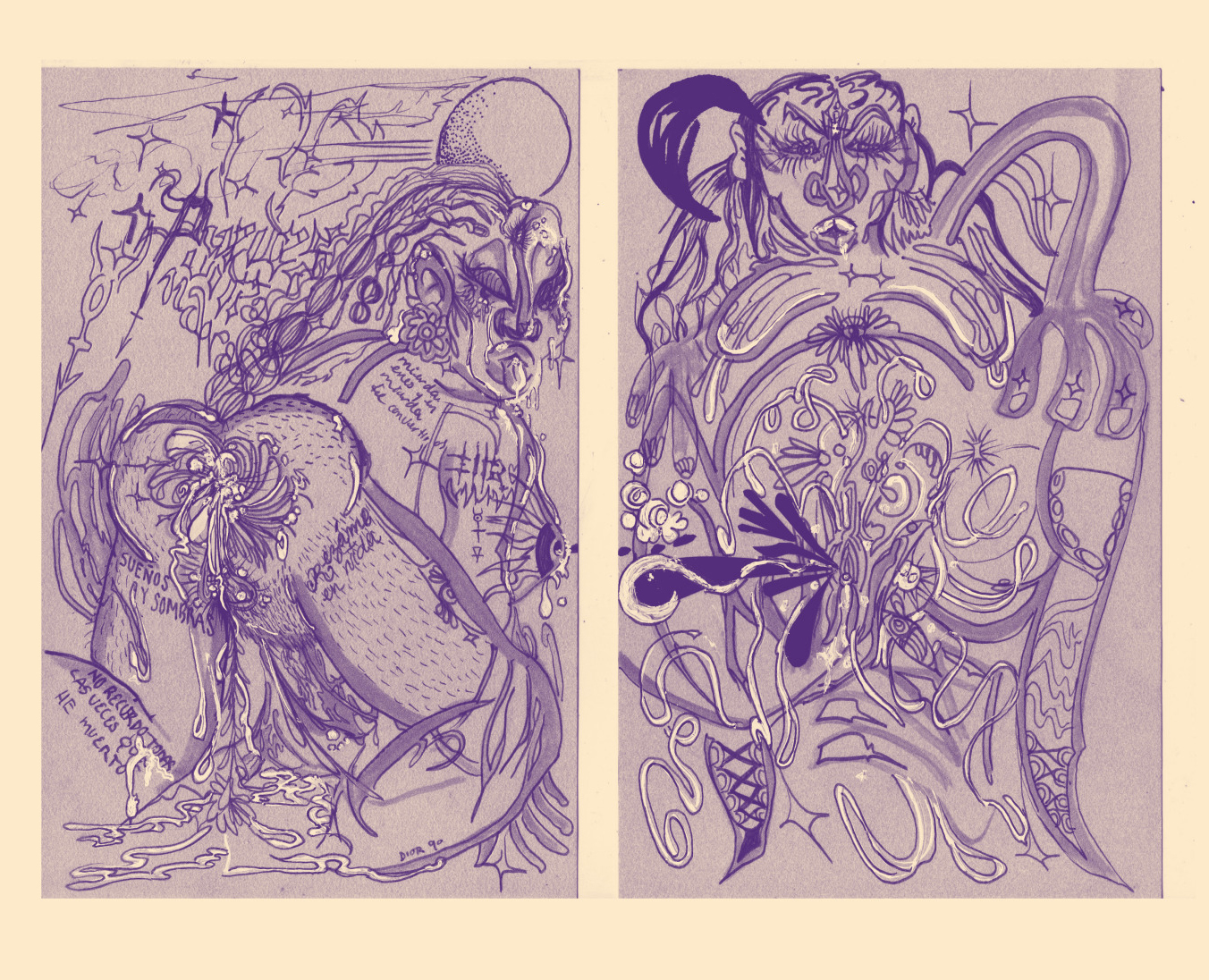

But ideas of racial difference did not disappear. Instead, the darker-skinned and darker-haired elements of society - descendants of Indigenous and Black people located almost inevitably in the lower economic strata - were looked down on by the lighter-skinned middle and upper classes as being vulgar, unruly, and dangerous, and collectively labelled as “negros” (blacks). “Negro” in Argentina is not understood necessarily as a reference to African ancestry but to a less defined idea of non-whiteness (which might include Blackness), entwined with notions of class, education, behaviour, and geographical origin.

The fact that this is not seen as a racial identity – by both white and non-white Argentines alike - combined with a dominant discourse of racial homogeneity, meant that the denial of racial difference and racism in Argentina persisted in the common sense, the media and even academic research until very recently. The recognition of racism against “negros” and Indigenous people, as well as Afro-Argentines, has been an uphill struggle, and even recent multiculturalist policy rarely addresses racism. There is a limited view that racism against Black and Indigenous people only occurs in instances of openly racist aggressions, while racist attitudes and expressions towards “negros” are mainly seen as manifestations of class-based prejudice.

The discourse of a white/European Argentina has considered whiteness not only as a racial identity. Like “negro”, it is entwined with ideas about social class, cultural capital, and urban life, and is presented as something that can be achieved with education and hard work. Yet, white Argentines of European descent strive to distinguish themselves from those they see as non-white, who find limited opportunities for social mobility.

Some Black and Indigenous people have mobilised politically and actively self-identify according to ethno-racial identities, either as Afro-descendant or as members of the over thirty Indigenous nations living in the Argentine territory - the largest of which are the Mapuche, the Kolla and the Qom/Toba. In the 1990s a constitutional reform recognized the pre-existence of Indigenous nations, which made historical reparation through land titling possible, for example for Mapuche communities.

Yet these policies have been limited and have not ended territorial struggles, some of which have resulted in deaths and are shaped by racist ideas of who can be a rightful landowner. Land struggles and a search for better education and employment have been at the centre of Indigenous migration to the cities.

While groups such as the Toba/Qom recreate an Indigenous life in the city, others are less aware or interested in their genealogies. However, they find a sense of familiarity with other Indigenous migrants in the city, as well as with the urban poor who are deemed “negros”. In fact, they are often labelled too as “negros” by the middle and upper classes, and some also end up self-identifying as such. Official figures from a 2004 survey indicated that 1.5% of Argentines self-identified as Indigenous, while the 2010 census for the first time in over a century included a question about Afro self-identification - with 0.4% of people self-identifying as Afrodescendant.