Brazil

Indigenous peoples in Brazil have been under sustained attack from the beginnings of the colonial period. They were systematically (and illegally) enslaved from early on until the late 19th century. From the 16th century onwards, they have been decimated by disease and driven from their territories and, in the 20th and 21st centuries, land-hungry “modernisation” and “development” have created ever-larger agro-industrial ranches and plantations. State policy has provided paternalist “protection” programmes for Indigenous peoples (who, according to the 2010 census, number about 800,000 individuals and comprise some 300 ethnic groups, speaking over 270 languages). At the same time, it simultaneously promotes the agricultural and extractivist industries that displace them and degrade the environment. From 2019, the right-wing leadership of president Jair Bolsonaro has given such industries free rein and provided a platform for anti-Indigenous racism to flourish, undermining Indigenous attempts to protect their lands, identities and ways of life.

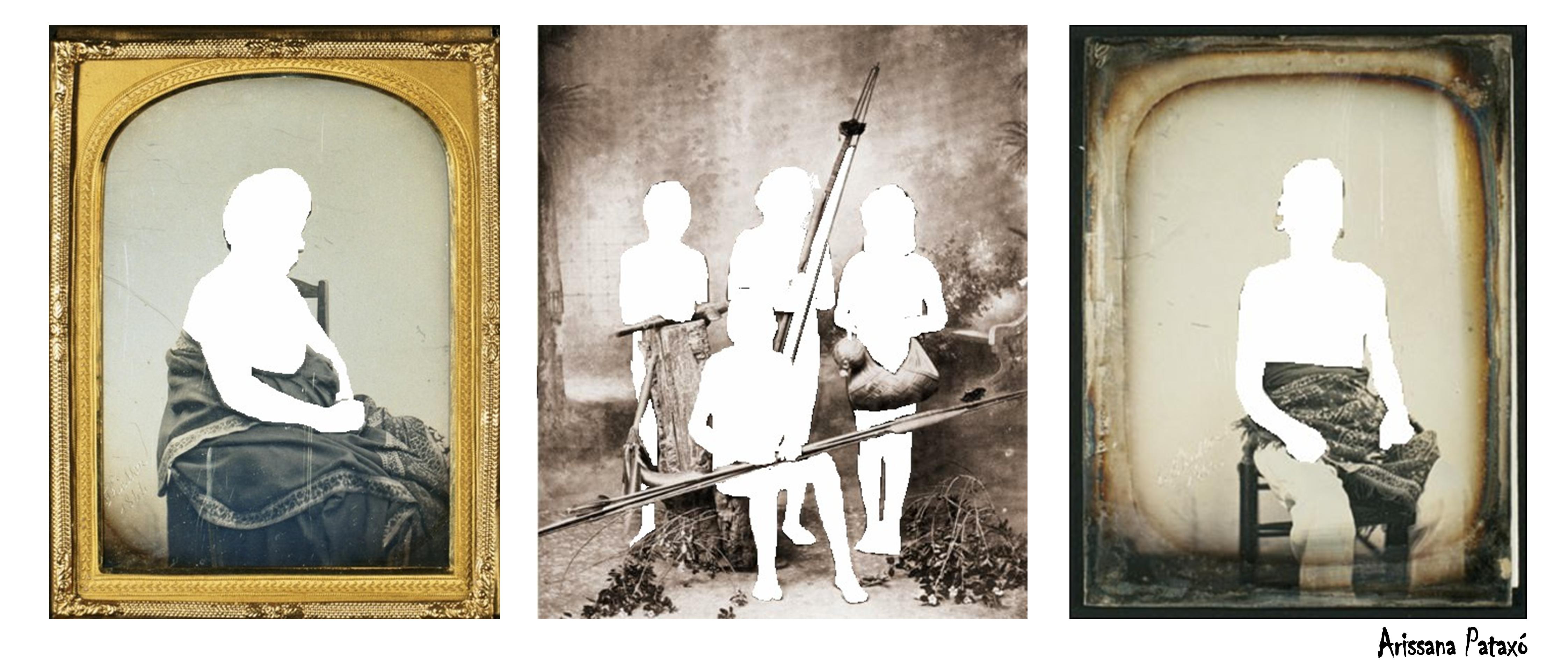

Yet, the figure of the “índio” has been central in elite imaginings of national identity since at least the 19th-century. In such nationalist myth-making, Indigenous people have been made to represent the uncivilised past from which “modern” Brazil has emerged, whilst living Indigenous people have been discouraged (and often forbidden) from speaking their languages, practising their spirituality or identifying as Indigenous. Perceived as destined to die or be assimilated and vanish, Indigenous peoples have been rendered so invisible that even racism against them is largely ignored. The prolific scholarship on racism in Brazil, for example, hardly mentions Indigenous peoples, whilst the country’s main anti-racist policies have been directed almost exclusively at Afro-descendants. Racism against the Indigenous population is rarely named as such and is marginal to the political agenda.

Indigenous resistance began to take on national-level dimensions towards the end of the 20th-century, with the debates around the 1988 Constitution. Recently, Indigenous mobilisation has increased in the face of the greater threats they face. In the last 10-15 years, Indigenous resistance has also found new and potent expressions in visual arts, literature, cinema and music, with land and identity being central themes. The arts has proven a fertile ground on which to cultivate challenges to racist stereotypes that consign Indigenous people to the past or to the jungles, that depict them as on the edge of physical and cultural extinction, and that deny them a place in the present and future of the nation.

Jamille Dias, Lúcia Sá, Peter Wade