Many racist comics try and depict a clash between racialised others, who are presented as backward or belonging to the past, and an idealised vision of modernity, one based around white and/or mestizo understandings of temporality and progress. Comics in this section both highlight such racialised temporalities and also depict positive visions of race in relation to alternative futures.

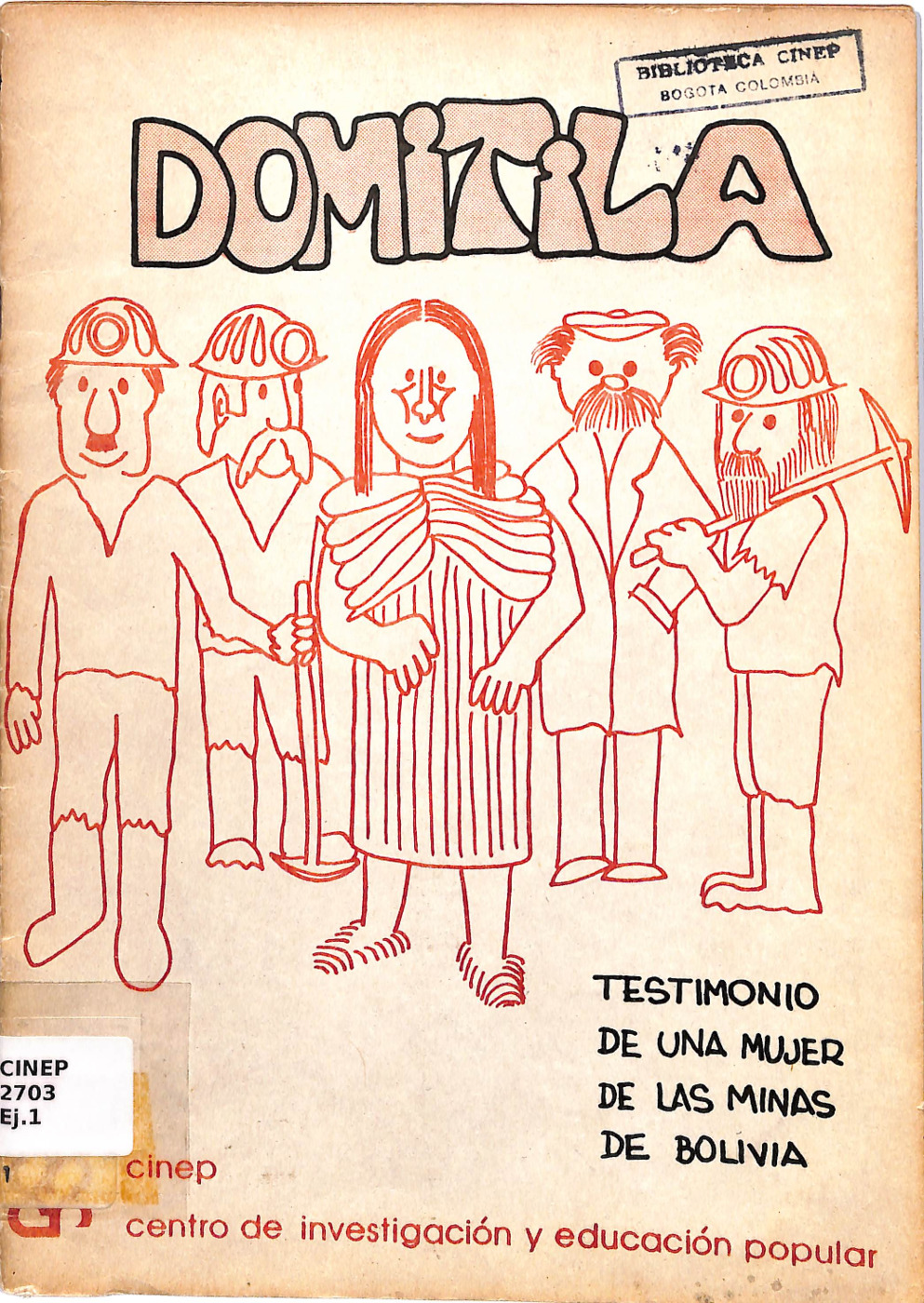

Domitila is a comic booklet produced in Colombia in 1979. It depicts the life and activism of Domitila Barrios in the mines of Bolivia. Her testimony at the 1975 UN Women's Forum highlighted the plight of Bolivian miners around the world. Edited by CINEP, a Jesuit organisation influenced by liberation theology, the comic presents Domitila as a spokesperson for rights and a class-based advocate for social justice. Although the critique of racism is not explicitly addressed, there are subtle hints that suggest its presence. In one scene, Domitila confronts Bolivian dictator Hugo Banzer, pointing the finger at him while criticising his use of the media to portray her community unfairly. Banzer reacts defensively, ignoring her words. Domitila denounces the president's television as alienating rather than educating, emphasising the need to be heard and recognised in her own voice. The comic concludes with a reflection on popular organisations inspired by Domitila's history as an Indigenous woman.

Malena Bedoya

These three images, “El teléfono fantasma” (1901), “Un chasco negro” (1918) and “Runtanos de tuerca y tornillo” (1929), are thematically linked by the rise during that period of modern technologies, such as photography and telephony, which were invented in Europe or North America and spread quickly across the world – along with the comic-strip itself.

“El teléfono fantasma”

“El teléfono fantasma” (the telephone ghost) is a comic-strip from Caras y Caretas, an Argentinian magazine of political satire and topical issues. Telephones began to be installed in Buenos Aires in 1881 but were not common in private houses by 1901. The comic-strip’s attempt at humour depends on the assumption that Black people, especially in their stereotyped role as manual and service workers, were stuck in a “primitive” state where modern technology appeared to them as amazing and perhaps threatening. The comic’s title implies that the Black cleaner sees the suited figure as a ghost, hence his shock.

“Un chasco negro”

“Un chasco negro” (a black disappointment) appeared in the magazine, Bogotá cómico. The unsigned story highlights photography, which was widespread in Latin America by 1918. Studios offered portraiture services at accessible prices, which gave the working classes the opportunity to present a carefully controlled, smart appearance. Deborah Poole relates that Lima studios at this time often altered photographs to lighten the skin tone of darker-looking subjects. The supposed joke in this Colombian comic relies upon portraying the Black man as ignorant, because he is not familiar with a photographic negative, but also as pretentious, donning a top hat and dress coat for his portrait and being thrilled by the apparently magical whitening of his “accursed hide”.

“Runtanos de tuerca y tornillo”

“Runtanos de tuerca y tornillo” (proudly from Tunja - runtano is a Colombian term for people from the Andean province of Tunja) comes from the magazine Fantoches, a Bogotá magazine of political satire and topical issues. The story refers to the creation in 1929 of a national identity card system, which required a photo and fingerprints to be taken from citizens. Debate emerged about whether the innovation would produce a more, or less, democratic outcome. Against the policy, Conservatives claimed the rural working classes, in their ignorance, would fear the camera and not obtain ID cards; Liberals responded that this was just self-serving elites trying to avoid what would be a democratic opening of the electoral system, by portraying Colombia’s working poor as savages who could not be civilised (as depicted satirically in the comic). In terms of racial identity, the old men in comic are not identified as Indigenous, but their attire and provincial origin, plus the lower-class status indicated by their illiteracy, clearly suggest Indigenous origins.

These items all reply on the common association in Latin America of whiteness with modernity and progress, while Blackness and Indigeneity are linked to the past and “primitiveness” (see the Temporalities section). In this view, Black and Indigenous people are ill-adapted to modern society and are destined either to die out or to assimilate, losing their Black and Indigenous identities and becoming whiter, if not physically - like the Black portrait-sitter in the photographic negative - then socially in terms of their behaviour. Anthropologist Michael Taussig observes that Westerners are often amused and reassured by the apparent fascination with modern technology shown by people they class as “primitive” or at least not as “modern” as they are. This amazement is taken as a testament to the apparently magical powers of Western technology.

Peter Wade

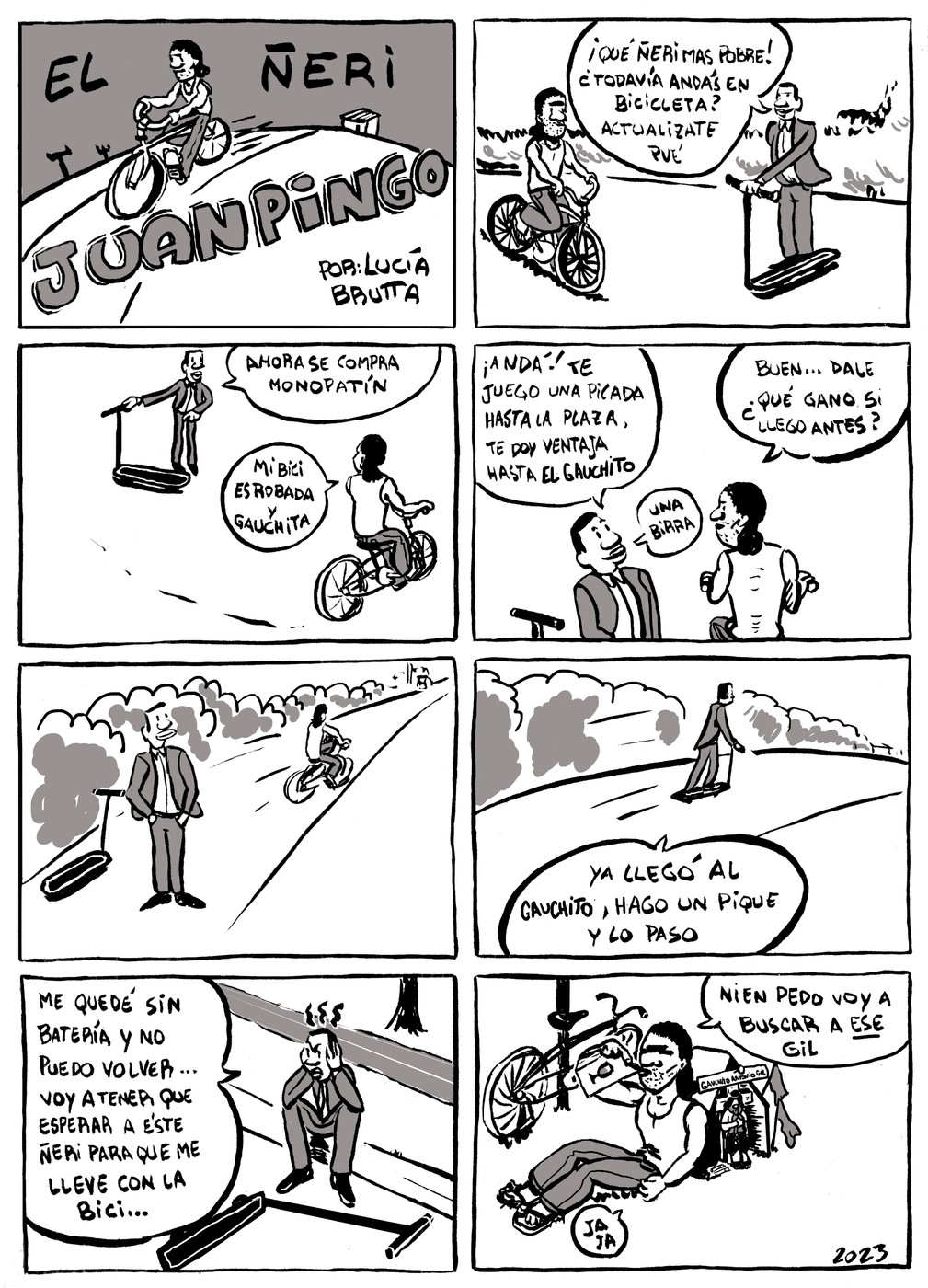

This comic, commissioned for this exhibition, is a response to the 1941 comic strip "El Gaucho Juan Pereya" by Pedro Gutierrez published in the magazine Figuritas, in which a wealthy rural landowner challenges a gaucho to a race in which he will drive his car and the gaucho his horse. The latter is victorious after the landowner gets a flat tire. Here Lucía Brutta plays with a contemporary vision of this tension between temporalities, in this case the electric scooter and the self-pedalled bike. The contested nature of modernity is also present in her humorous references to Gauchito Gil, Argentina’s most popular folk outlaw saint, a symbol of resistance to structural hierarchies ("gil" in Argentina is also slang for "fool" or "idiot"). The references to race, as in many situations in Argentina, are subtly tied up with class difference.

James Scorer

The comic strips of El Perú Ilustrado (1887-1892) were referred to as "epigramáticas" at the time, signifying that they were considered short and satirical narratives. Belisario Garay, the illustrator of this publication, crafted six illustrated tales depicting the occurrences surrounding the use of this technology upon its arrival in the city of Lima. The artist portrays the potential consequences of communication without visual contact. The comic serves as a cautionary tale, urging us to avoid confusion and deceit: what could happen if we cannot see each other? In the second panel, we encounter a Black man who expresses surprise at being offered a "position" - a job - as an officer. His posture appears relaxed, with his guitar and hat visible on the floor. The character's remark is aimed at the readers, highlighting the potential error of the caller and normalising the societal roles assigned to these racialised individuals. The stereotype and racial bias towards this Black character are triggered, associating him with the traditional folkloric image of music, rather than any other possible occupation.

Malena Bedoya

“Don Zenón, Petronila, and Trampolín” (1940) is a comic strip from Palomilla: revista peruana para los niños, whose author is unknown. The plot features a middle-class Black family in Lima, always ready to enjoy urban leisure: dances, cinema, theatre. The racist representation of Black bodies is manifested through a drawing that exaggerates certain features, almost turning the characters into apes. Zenón, the father, and Trampolín, his son, dress as sailors, while Petronila is always elegantly dressed. In the story, Petronila finds an advertisement in the newspaper looking for actresses and decides to participate. Upon arriving at the casting, she mentions that she is there because of the advertisement for "looking for a star." However, the person in charge only offers her a role in a troupe in the movie "The Fall of Ethiopia." This story is loaded with racism, from the animalized representation of bodies to allusions to servitude and the role offered to Petronila, who cannot be an actress but only a background character in a troupe of Black characters.

Malena Bedoya

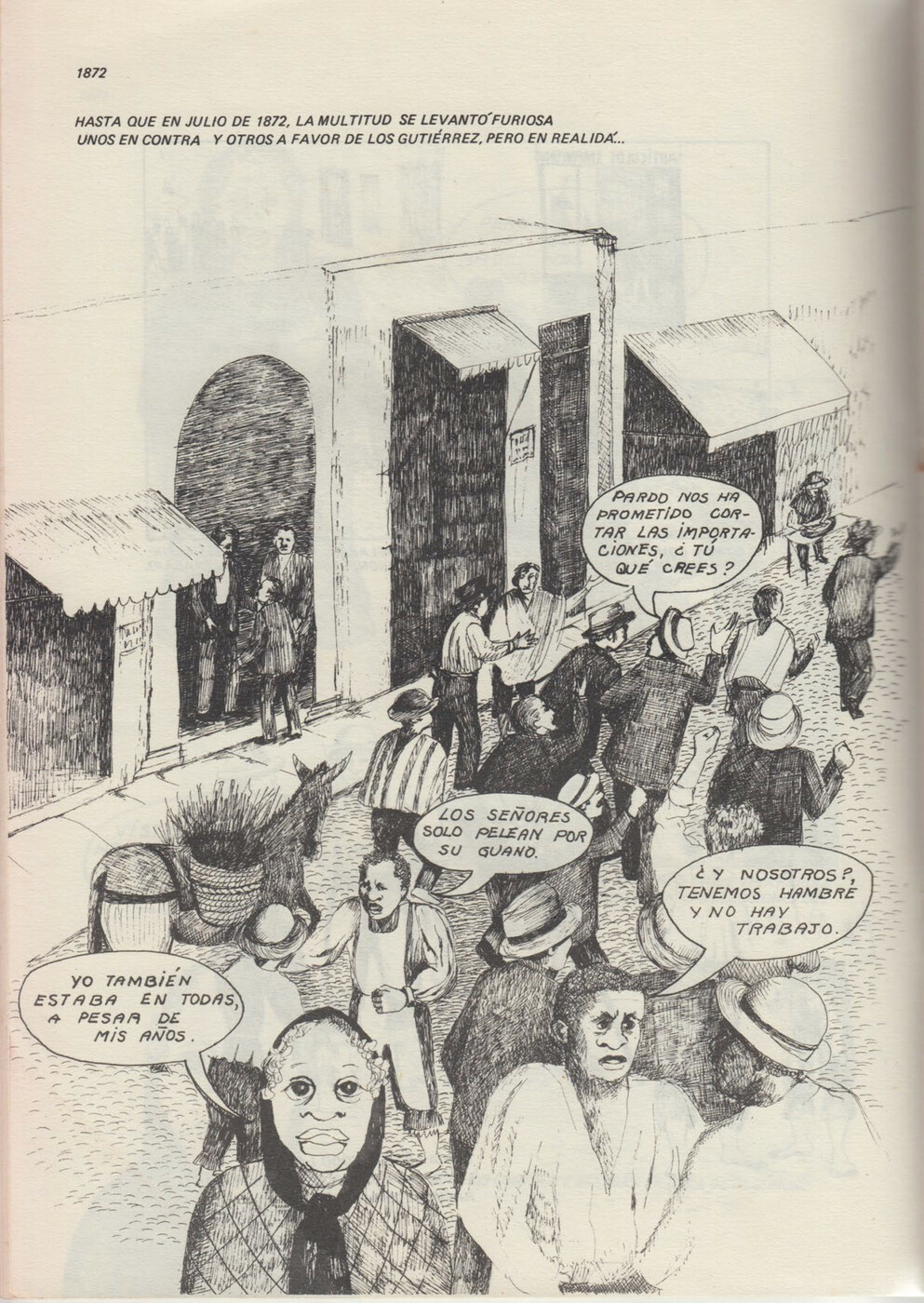

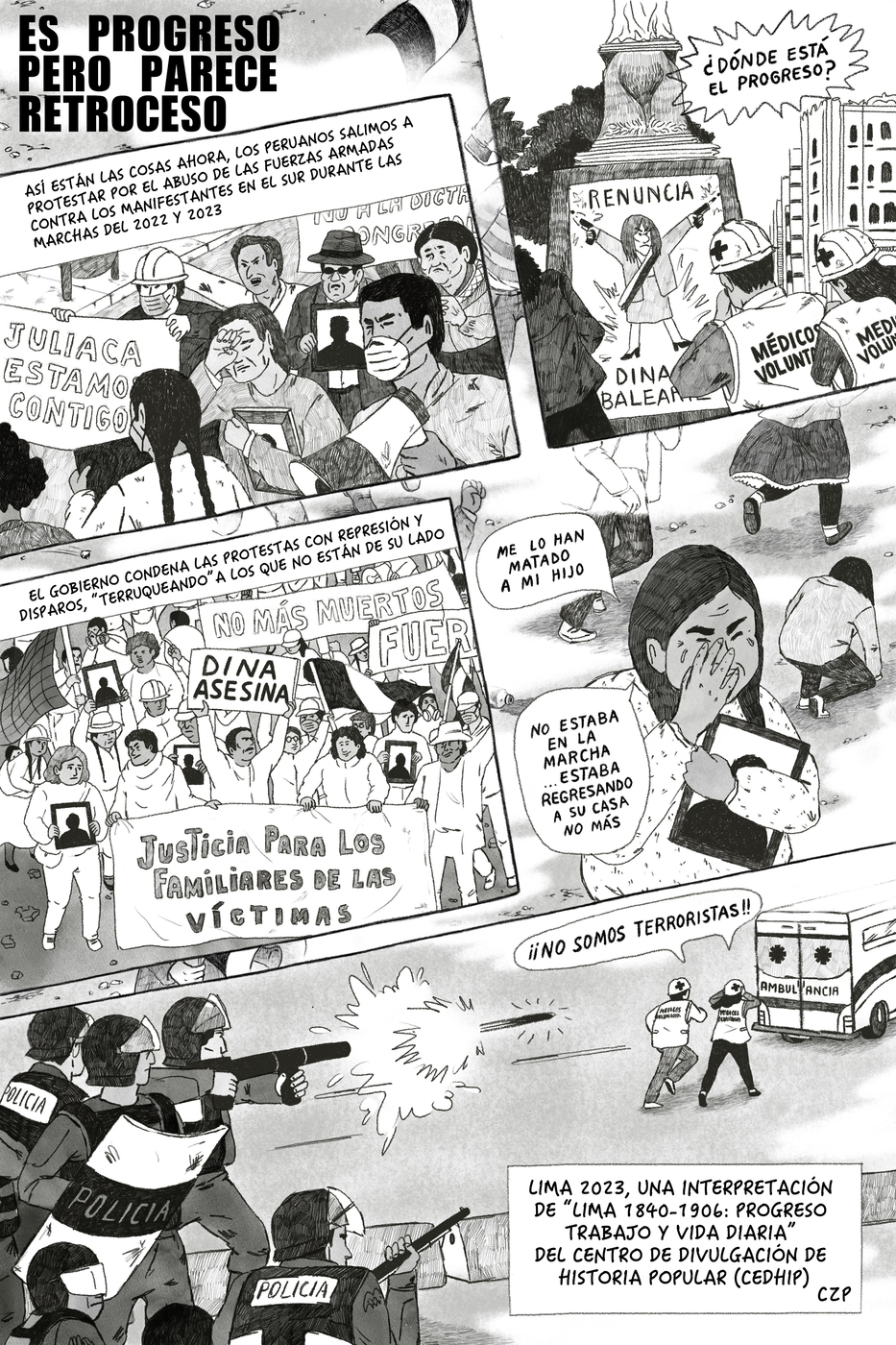

Lima 1840-1906: Progreso, Trabajo y Vida Diaria (1979) is the first comic book from the Centro de Divulgación de Historia Popular (CEDHIP), founded in 1979 in Lima. Illustrated by Marisa Godínez with historical research by Margarita Giesecke, the comic features Paulina, a Black woman narrating her life in 19th-century Lima, and her granddaughter Luzmila, who narrates the transition from the 19th to the 20th century. The artist uses colloquial language emphasising the characters, as well as employing visual references such as folkloric prints and 19th-century photographs to depict Lima's environment. Urban life highlights daily life, commerce, and consumption, as well as class differences. Paulina criticises the notion of "progress," blaming the political class, represented by white-mestizo men, for social and economic inequalities. This protagonist focuses particularly on the boom of guano, its social consequences, Chinese and rural migration to Lima. In this image of the strike due to the guano crisis of 1872, Godínez decides to foreground Black workers. In the second part, the comic continues with the granddaughter Luzmila who will recount the War of the Pacific and the boom and crisis of saltpetre.

Malena Bedoya

Since 2019, the economic, social, and political crisis in Latin America has deepened, manifesting itself through protests in countries such as Chile (2019), Ecuador (2019-2022), Colombia (2019-2020) and Bolivia (2019). In Peru, the popular revolts of 2021 exposed political corruption and abuses of power. The country's main cities became the scene of clashes between the population and the forces of law and order, particularly affecting the most economically vulnerable sectors. In response, the government intensified repression, resorting to disproportionate use of force and causing serious harm to the civilian population. Many of those affected belong to racialised communities and reside in the most impoverished areas, making them targets of an oppressive system. In this depiction, Zavala evokes the memories of the victims and underlines how, under the accusation of "terrorism", human rights are violated. It is essential to highlight the role of structural racism in these crises, as racialised populations are often the most affected by state violence and socio-economic marginalisation. In many cases, Indigenous and Afro-descendant communities face systematic discrimination that exacerbates their vulnerability to government repression and deepens existing inequalities.

Malena Bedoya