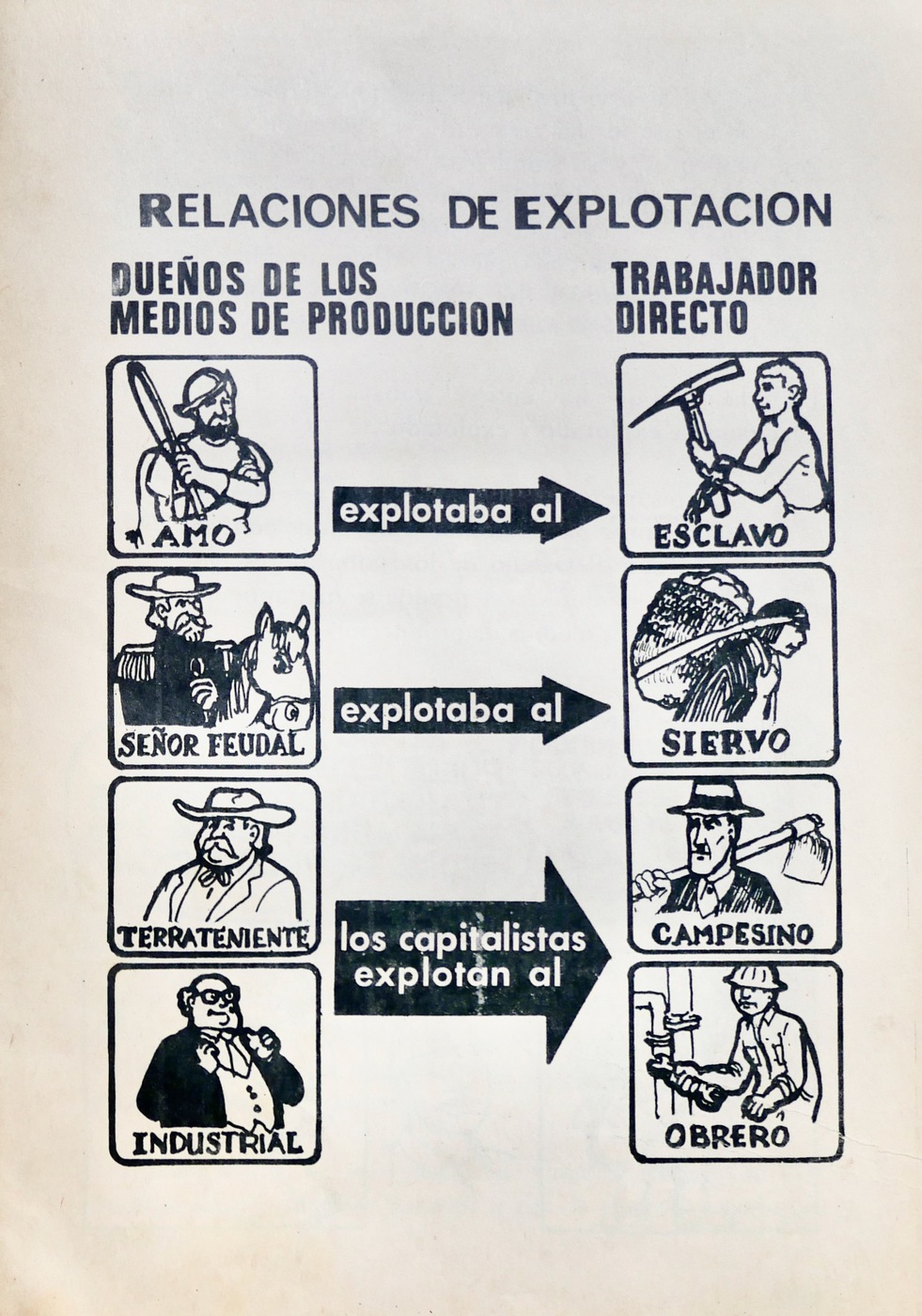

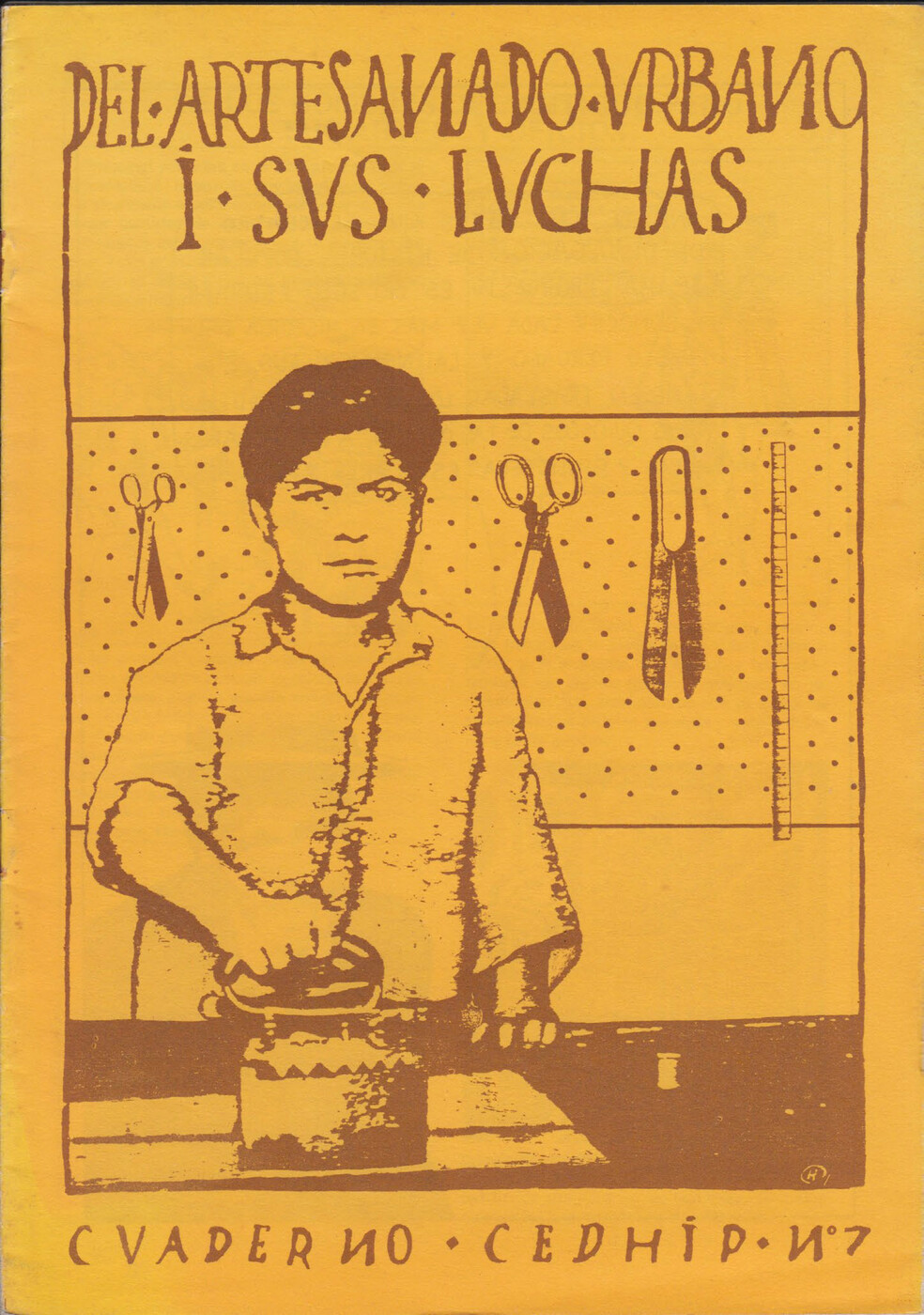

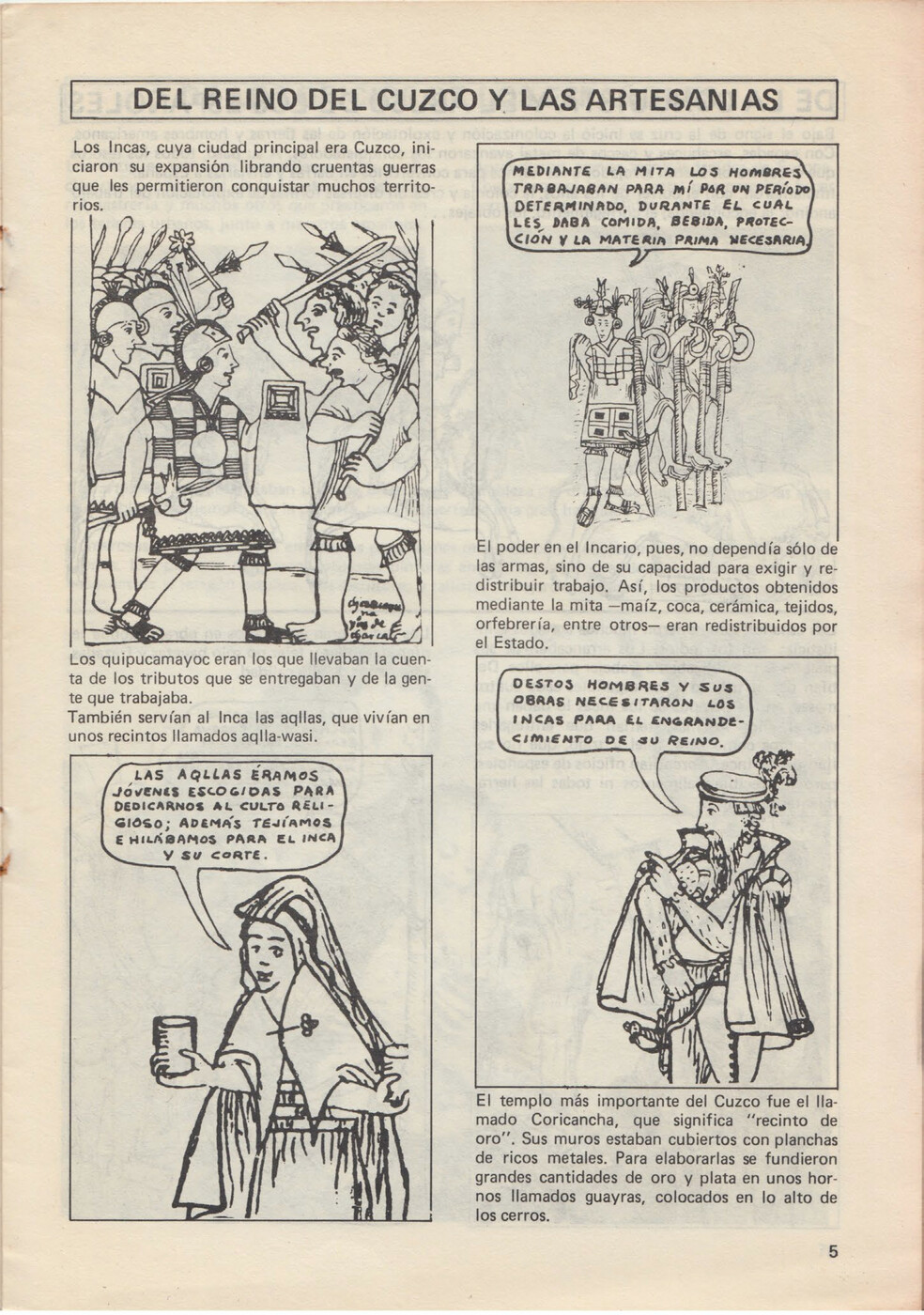

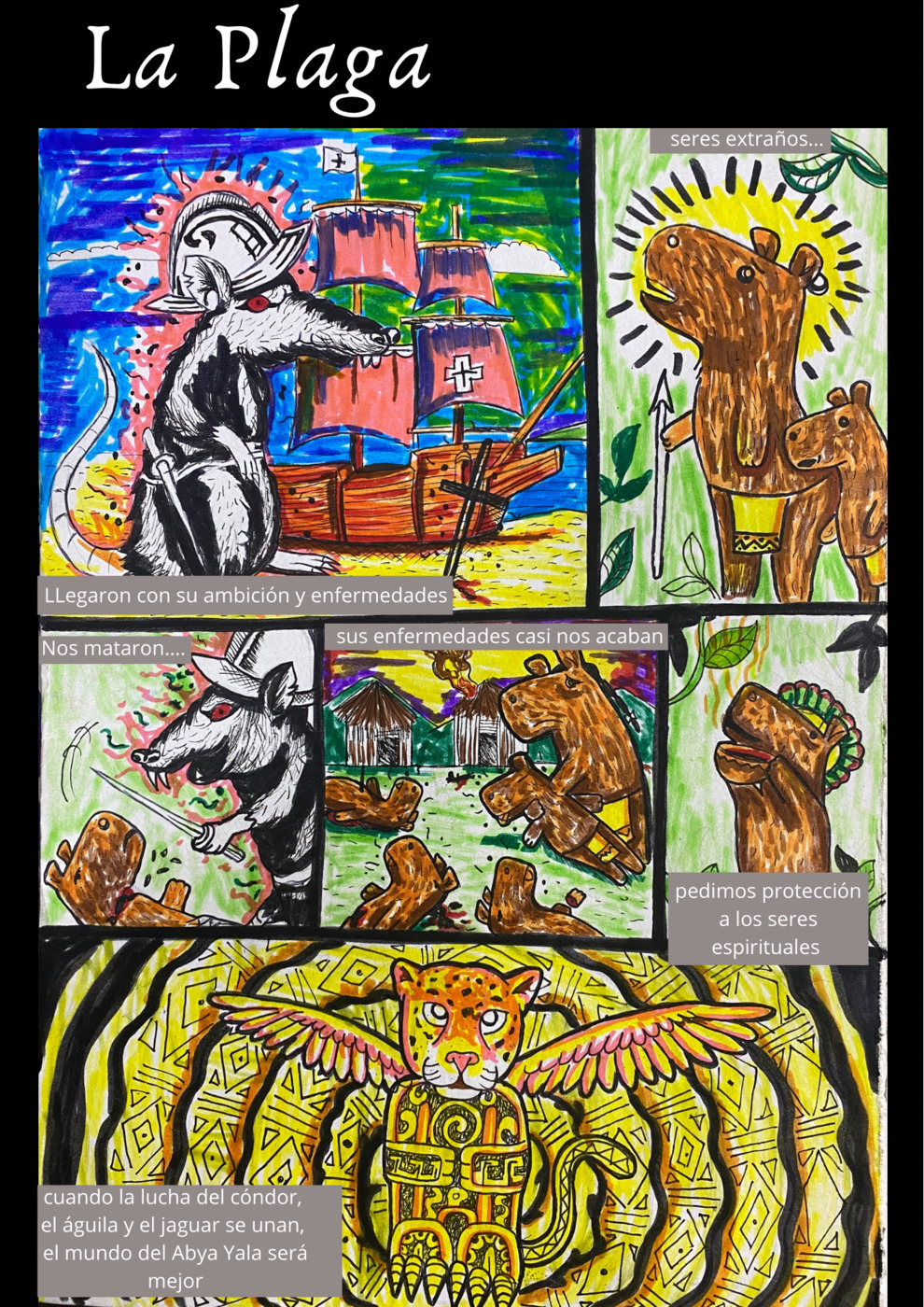

Del Artesanado Urbano i sus Luchas is a comic by CEDHIP, published in 1983 of unknown authorship, intertwining elements of the Primera Nueva Corónica y Buen Gobierno by Guamán Poma de Ayala with photographs and illustrations. From the Inca era to the 19th century, it highlights the role of Indigenous and black populations in artisanal crafts. The first part, "Del Reino del Cuzco y las Artesanías" illustrates the Inca conquest with precise references to the Corónica from Inca struggles to the arrival of the Spanish. The use of speech bubbles and “costumbrista” prints brings the characters to life and lends authenticity to the Inca past, presenting it positively. This approach contrasts with the representation of the colony and republic, which will be addressed in later pages, where the presence of Indigenous and black people fades into history and dissolves into the concept that encompasses them, the notion of the working class or the people in their social struggles.

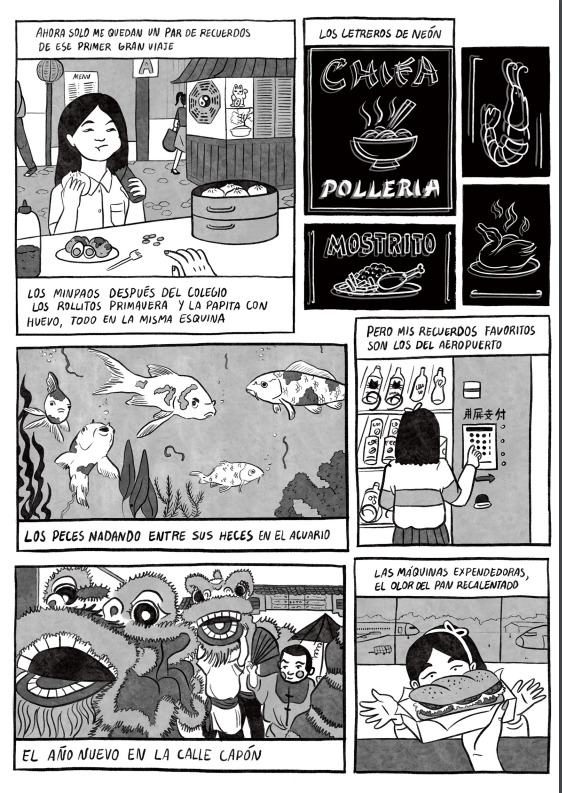

Malena Bedoya