Concepts of race in Latin America – as elsewhere – have long been dependent on notions of racial hierarchies. This section highlights some of those hierarchies, demonstrating how particular visual beliefs and expectations about racial identities have been both reproduced and challenged in comics.

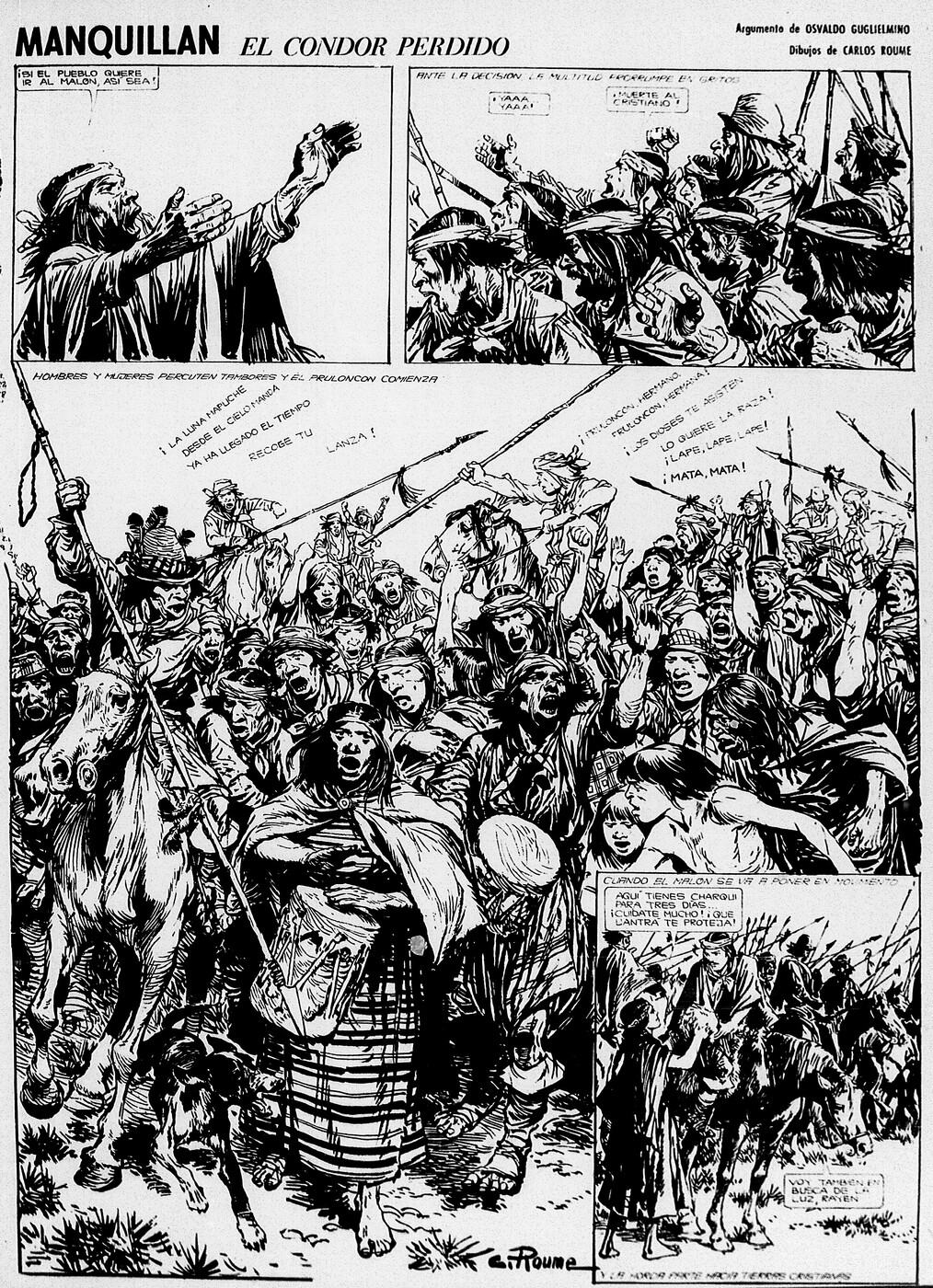

Manquillán, el cóndor perdido (1969-1970), written by Osvaldo Guglielmino and drawn by Carlos Roume, was published weekly in the "Rural" supplement of the Argentine newspaper Clarín. The comic’s depiction of nineteenth-century struggles over the pampas were published alongside articles about the state of the country’s agricultural heartlands, a site of political tension between those wanting to protect working-class agricultural labourers, and those calling for the mechanisation of the countryside in the name of development.

Guglielmino’s script draws on the historical figure of Eugenio del Busto, a white man captured and raised by Indigenous tribes as a child in the early nineteenth century, but who, after being taken back by the Argentine army, subsequently fought against Indigenous people in the euphemistically named "Campaign of the Desert", a state-led military operation that decimated the Indigenous population. The comic is noteworthy for how Roume’s artwork generates a sense of Indigenous energetic power, evident here in the way the eye moves from the beating drum, up the spear, across more spears aligned with the crowd’s cries, and then back down through the crowd to the woman and her drum.

James Scorer

Commissioned for this exhibition, Jesús Cossio’s response to the above page from the Argentine comic Manquillán relies on creating a set of energies different from those found in the earlier comic, in which Indigenous people gather for a raid. Here, Cossio captures the angry racist discourses of Lima’s wealthy sectors, evident in the conversations of those attending a high-society cocktail party. Cossio’s meticulous drawings convey a sense of this social group via clothing and conversation rife with racialised vocabulary. The various expressions of those gathered, conveying sentiments of self-satisfaction, disdain, and even horror when speaking of Indigenous populations in Peru, also highlight how structural inequalities are shaped around racisms that are self-perpetuating. Cossio’s image is a reminder that race should also be thought of in terms of whiteness and mestizaje, not least in terms of those in positions of power failing to question their own class and racial privilege.

James Scorer

"El Último Pago" (1891) appeared in the newspaper El Zancudo directed by Alfredo Greñas. The journalists of this newspaper stood out for their fierce opposition to the conservative regenerationist regime established in the country after 1886. In this representation, the Colombian people are personified in the form of a skeleton which, in the editorial accompanying the image, explains how, due to the government's economic policies, the population is forced to hand over "the last thing it owns", symbolised by its skin. It also highlights that the situation of the people is "even more unfortunate than that of the Indigenous people at the time of the conquest and colonisation". In the vignette, the skeleton points to two ragged beggars behind him, standing by a prison door, representing annihilated industry and property. Although no explicit mention is made of their racial origin, the clothing - especially the women's - of espadrilles, ruanas and hats suggests an association with the Indigenous. In this way, Greñas employs certain visual elements to represent the misery and poverty embodied in these racialised subjects.

Malena Bedoya

The image appeared in 1903 in Caras y Caretas, a weekly Argentinian magazine of political satire, humour and topical issues. Drawn by a little-known artist, it appears on its own without context. While it is difficult to interpret, it shows that the existence of human “races” was taken for granted. As indicated in the Introductory text on race and racism in Latin America, scientists at this time wrongly believed that human beings could be divided up into a number of “races”, some innately superior to others, defined by anatomical differences that also determined intellectual, moral and behavioural traits. These drawings reproduce the idea of human “races”. But they also undermine it with humorous reference to “races” labelled Diabolical and Horse. Also, the drawings do not always conform to dominant racial stereotypes of the period: e.g. the Ethiopian is not a stereotypical African, nor is the Caucasian a stereotypical European. The “race” labelled Modern is ambiguous, but is perhaps the closest to what might be perceived by readers as European and this clearly reinforces the idea current at the time that white Europeans were more “advanced” than other so-called races.

Peter Wade

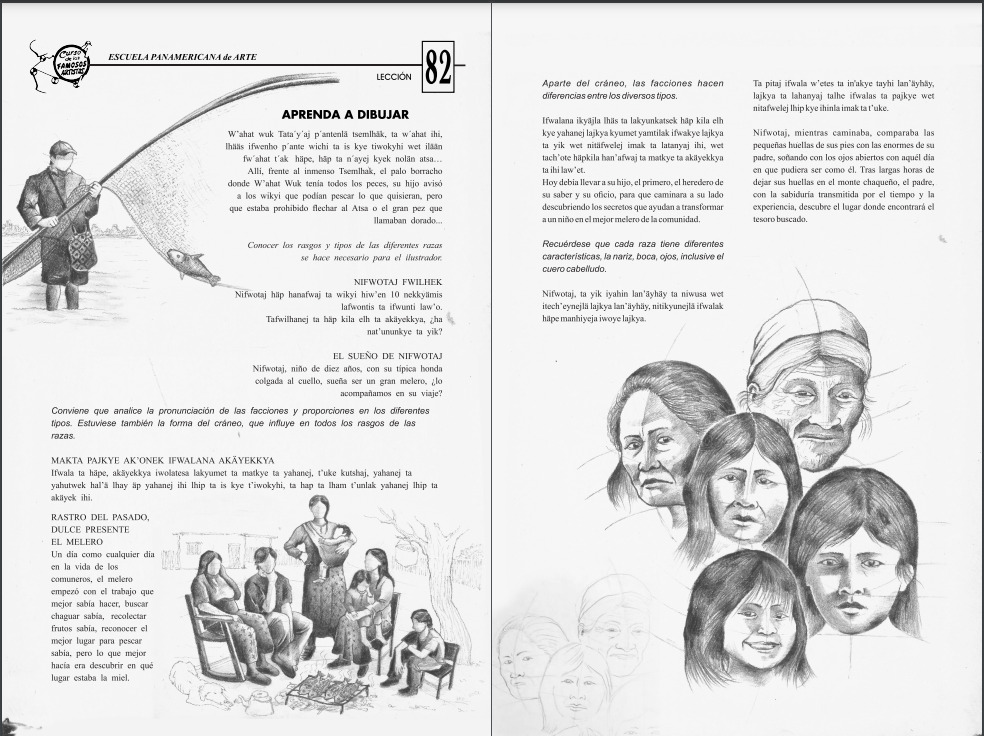

These pages are part of material produced by the Escuela Panamericana de Arte (Pan-American School of Art) for those enrolled on its comics course. Students received 15 folders with sheets totalling some 2,000 drawings. Using work by famous artists such as Hugo Pratt, Alberto Breccia, Carlos Roume, and Enrique Vieytes, and based, as Judith Gociol describes it, on "a classic approach with emphasis on realism", the Escuela taught different drawing and comics techniques, including focalisation, perspective, shading, and the human form. The pages shown here provide instructions on drawing faces of four racial groups, "white, black, yellow, and coloured", the latter referring to Indigenous populations. Alongside drawings reminiscent of spurious links between brain shape and personality, and other forms of scientific racism (see text on "Race" and Racism in Latin America), the text notes that "according to the canons of harmony, the white [profile] is the most beautiful". The sheet highlights how the comics world in the 1950s and 1960s reproduced racial hierarchies by fusing claims to scientific truth and (white) traditions of artistic and corporeal beauty.

James Scorer

These pages mirror the aesthetic of the instructions created by the Escuela Panamericana de Arte above as part of its comics course that was delivered during the so-called ‘Golden Age’ of Argentine comics in the mid-twentieth century. This work by the Salta-based collective Kalay’i, commissioned for this exhibition, highlights the shortcomings of the earlier set of instructions, not least the reproduction of stereotypical racial features as part of guidelines that also associate beauty with whiteness. In that sense, these pages provide alternative images of Indigeneity, whether via images of fishing practices or alternative instructions for drawing Indigenous faces, creating a kind of counter-visuality that combats the racism embedded in the Escuela’s instruction. But by including untranslated Wichi text they also highlight the limits of knowledge and what it is possible for the viewer to access: the person who does not speak Wichi must inform themselves of the language before they can fully comprehend the text.

James Scorer