Latin American comics have been effective at both documenting protests related to racialised territories, whether in rural or urban areas, and at themselves embodying protest. If lines in the land or street demarcate areas of racial exclusion, then lines on the page can become another means of taking back space.

Comics may be used as educational tools to support the organisation of resistance to injustice. This example arises from Participatory Action Research, a technique developed in the 1970s by Colombian sociologist, Orlando Fals Borda, to link research closely to community activism. In the Sinú zone of Colombia’s Atlantic coastal region, where the working classes are Black, Indigenous and dark-skinned mestizo people, Fals Borda and his colleagues encountered the artist Ulianov Chalarka. They asked him to work with members of the national rural union’s local branch to illustrate their stories of resistance to oppression by light-skinned landowners. The often-prominent role of Black women in activism is reflected in the story about Felicita Campos, who organised resistance in the 1920s, taking local demands for land to Bogotá. She won land titles for her community, but this proved a hollow victory in the face of corruption and continued abuses. A local Indigenous community joined the fight, fatally poisoning the local landowner in 1932. However, landowners continued the violent oppression. Felicita died in 1942, leaving her son to lead the fight and form a local branch of the national rural union: in 1972 they managed to regain control of over 60,000 hectares of land.

Peter Wade

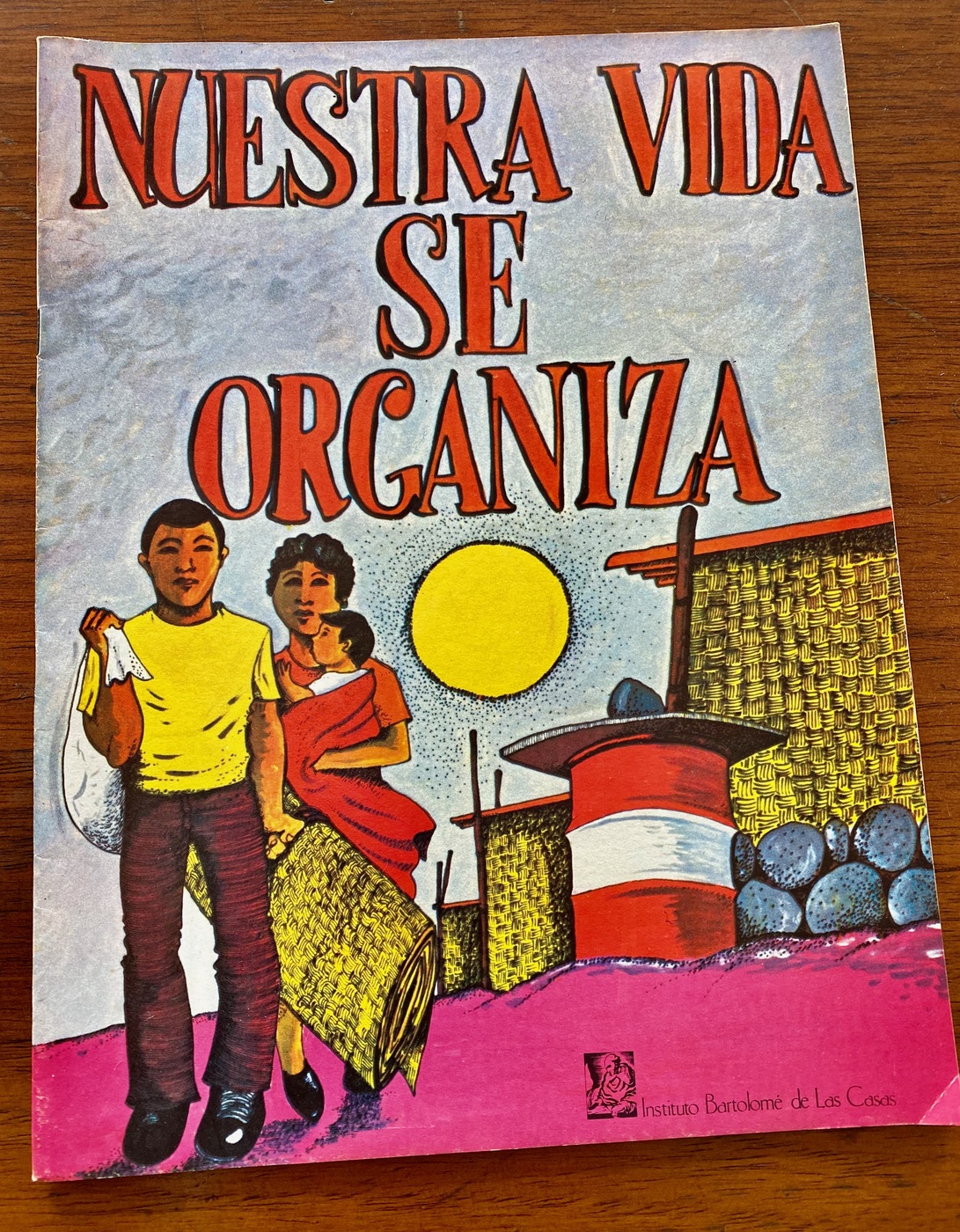

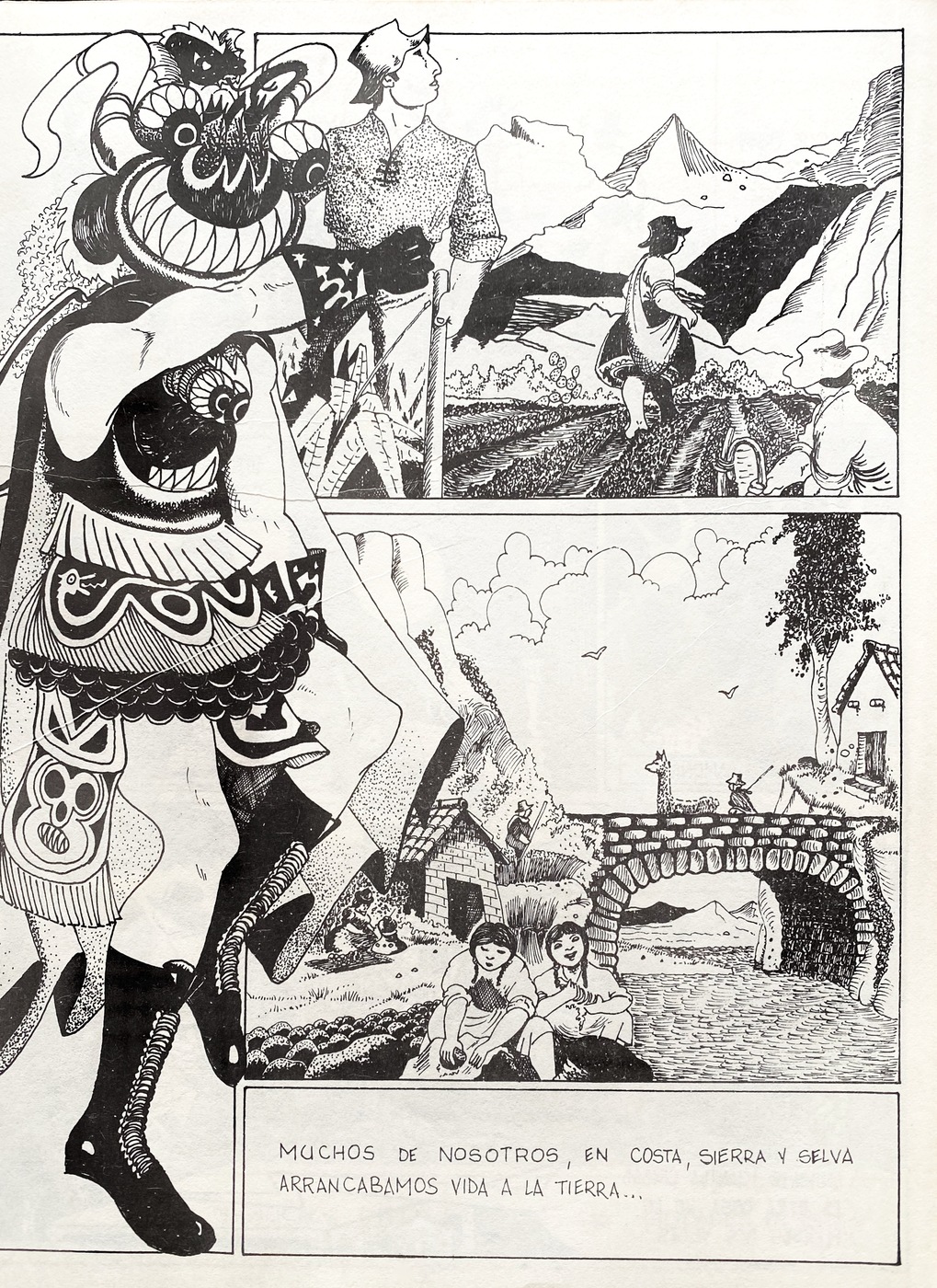

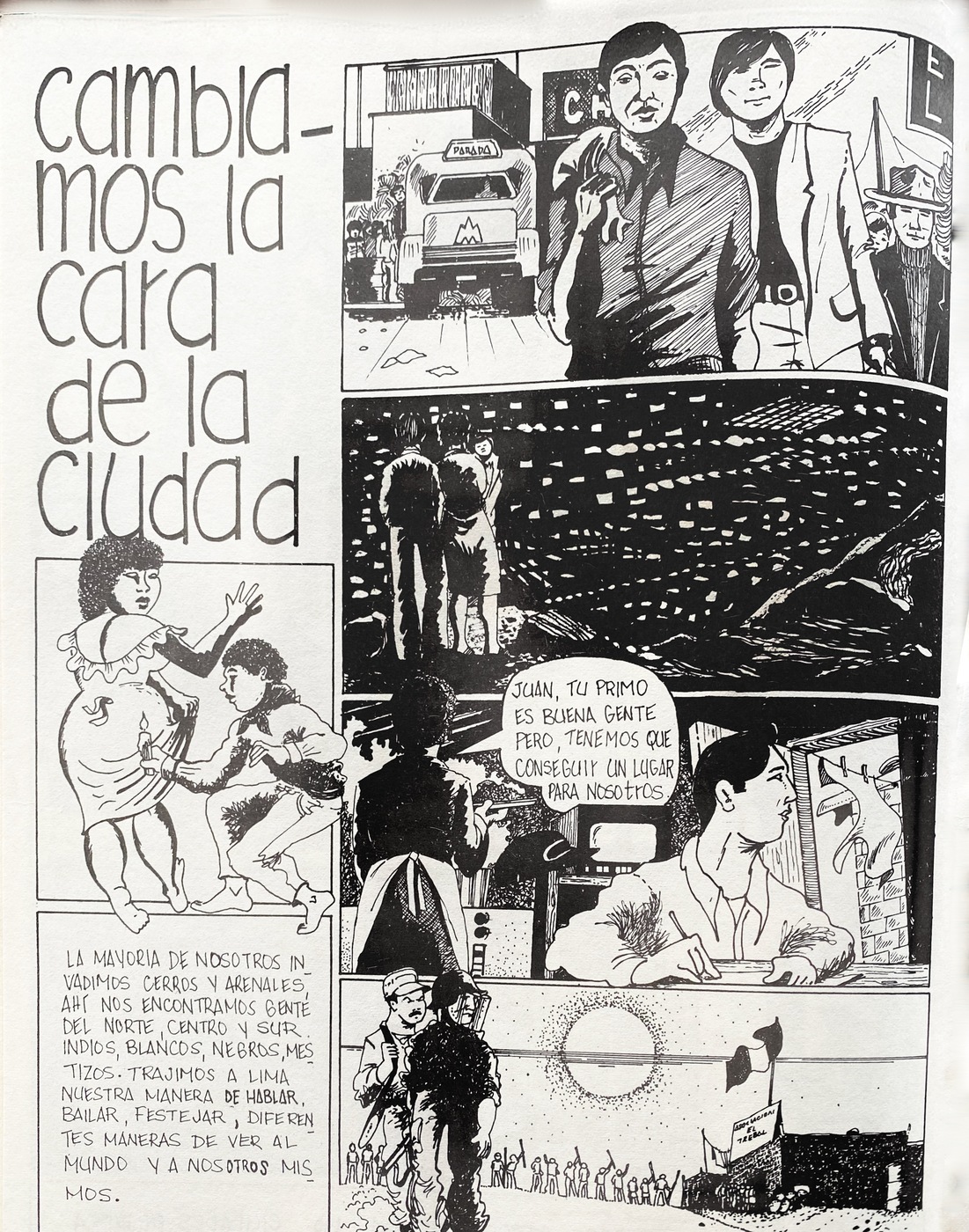

This 1985 zine, published by the non-profit, Catholic organisation Bartolomé de las Casas Institute, addresses the difficulties faced by Indigenous people when migrating from country to city. The first page included here presents a rural idyll of agricultural labour and Indigenous cultural practices. But subsequent pages demonstrate how corrupt landowners and state officials push impoverished people to Lima in search of better working conditions. The zine highlights the challenges of such rural-urban migration, whether in terms of lack of basic infrastructures, or the impact on a sense of self, both individual and collective. Though the publication positions the Church as a support mechanism within this dynamic, ultimately it emphasises the importance of collective forms of community mobilisation: inhabitants of informal settlements make collective decisions and pool their labour to improve access to water, drains, and electricity. Occupying the page-city, they also protest social exclusion and confront the state. But they also put bodies in space to highlight how migration challenges long-standing racial hierarchies, evident on a page showing Indigenous people dancing in the face of Lima’s cold-faced high-rise buildings, themselves the product, it is implied, of colonialism and US neo-imperialism.

James Scorer

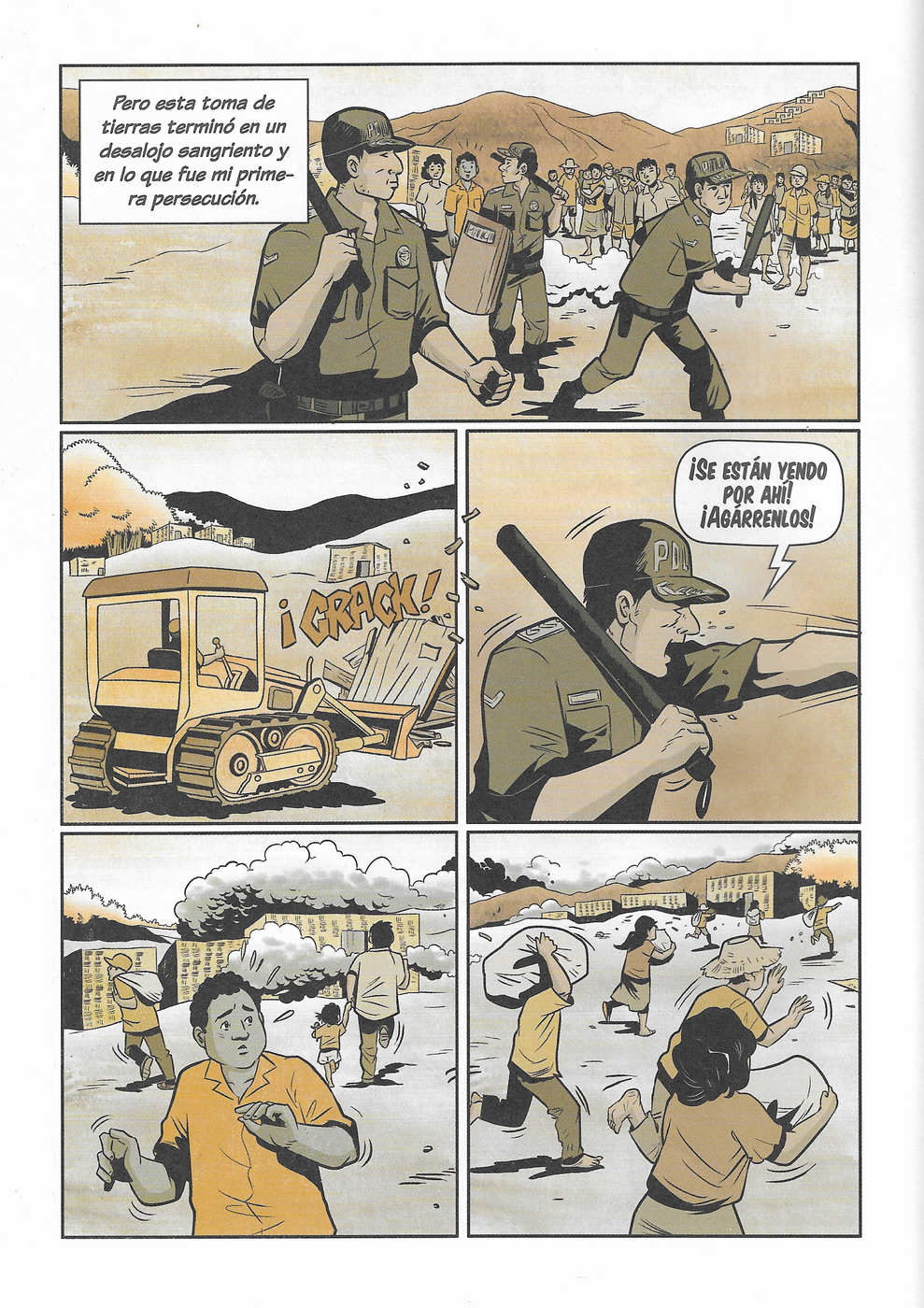

This comic reveals the deep structural oppressions and brutal state violence that Indigenous, Afro-descendant and peasant communities face in Peru. It also reflects how these populations resist such violence and work creatively for their communities and to promote social justice. It tells the story of Abelardo Zamora, a member of a large family including Tallanes, Afros, and indigenous people. Early on, despite facing social inequalities including difficulties to access proper schooling, his perseverance led him to acquire the skills of reading, writing, and arithmetic. At the mandatory military service, he experienced the fact that the Army is a space of discrimination and violence. Subsequently, he became involved in the peasant movement to reclaim land in upper Piura, resulting in being subjected to years of persecution. Engaging deeply in social justice advocacy, he served as a municipal councillor, advocated for Afro-Peruvian rights, and supported teachers' demands for which he faced baseless accusations punitively labelling him a terrorist. Upon being acquitted from the unfounded accusations, he constructed a school, implemented an intercultural education project, converted his home into a museum, and presently devotes himself to chronicling his hometown’s stories and traditions passed down by his grandmother.

Abeyamí Ortega

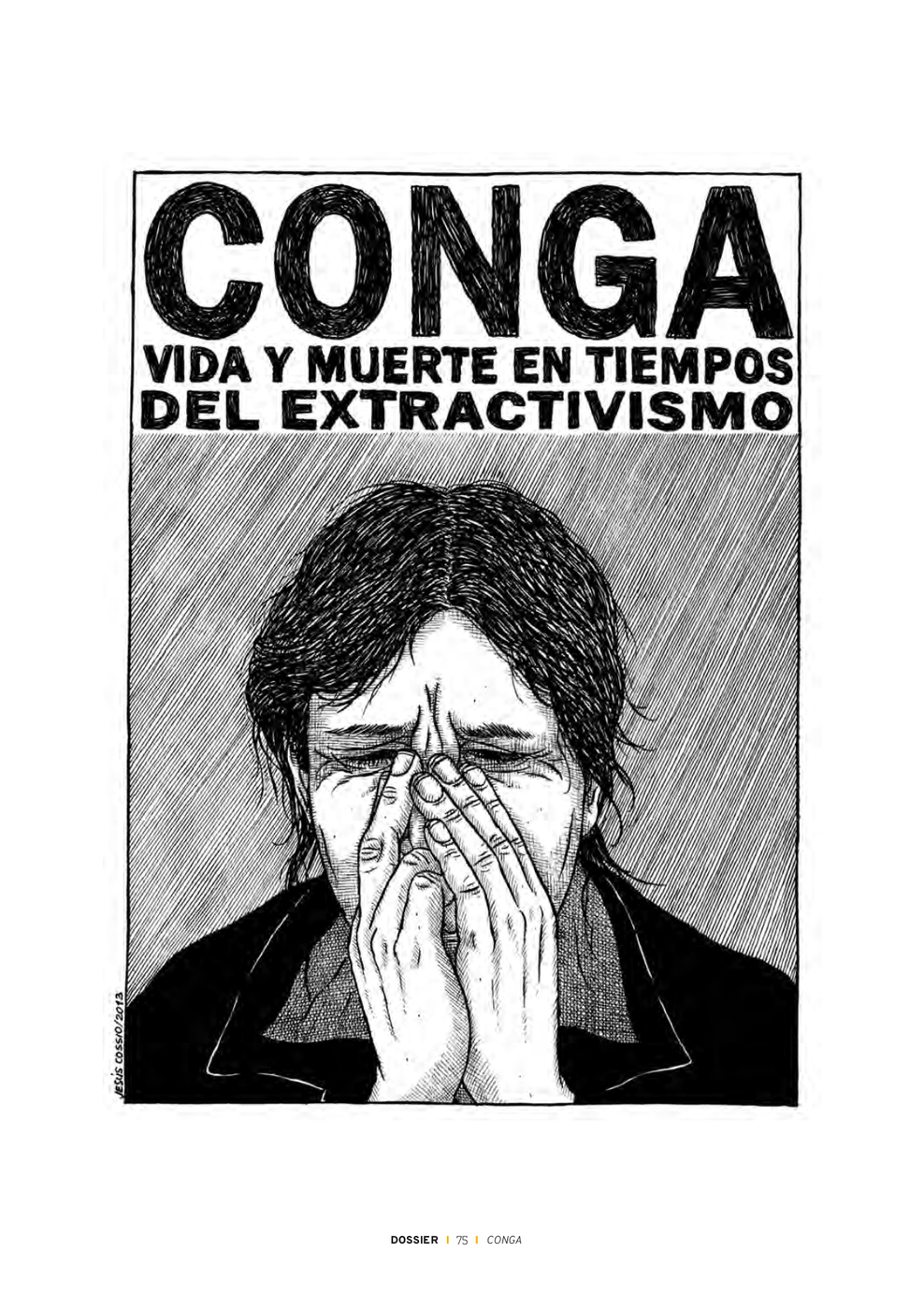

Jesús Cossio’s short comic Conga, first published in 2013 in the journalistic magazine Cometa and foreshadowing his work on The War Over Water, tackles protests against mining extractivism in Peru. The first page of the comic, visible via the link below, uses intricate, labour-intensive ink drawings to depict local people in tune with their environment: the artist’s intricate lines and hatchings bond bodies and landscapes. Residents express concerns about the impact of gold-mining operations on local water sources in Cajamarca, in northern Peru. Carried out by a conglomeration of US and Peruvian companies, the operation highlights the transnational nature of large-scale mining. Later in the comic, the Peruvian state aggressively puts down the protests, accusing the dissenters of being "against the progress of the country". The discourse of anti-mining as anti-national fails to acknowledge the significant negative impacts of such mining practices on those who live on the frontiers of extractivism, including Indigenous and Black populations. These people suffer chemical contamination of water sources, enforced changes to labour practices, and cultural and physical displacement. Conga puts on display bodies too often invisible to those living far from zones of extraction.

James Scorer

Read Conga: Vida y muerte en tiempos del extractivismo in full

![The cover of a book, titled “Graphic history of the fight for land [rights] in the Atlantic coastal [region of Colombia]”. The drawings are attributed to Ulianov Chalarka and the book itself to Fundación del Sinú. The cover shows four title pages, each relating to short stories in the book. They are titled: “Tinajones: a village fighting for its land”; “El Boche: a rebel peasant farmer from the Sinú”; “Lomagrande: the bastion of the Sinú”; “Felicita Campos: the woman peasant farmer fighting for land”.](https://www.digitalexhibitions.manchester.ac.uk/files/large/1dd75d212eb1a766a5072292739864659d020e12.jpg)