This exhibition presents the work of the project Comics and Race in Latin America (CORALA), funded by the AHRC. It includes entries drawn from the archive and work by contemporary Latin American artists, including some commissioned for this exhibition.

Comics and race

Comics, like all cultural forms, have long had a troubled relationship to race. Racism in comics has often been very visible and very violent. In part, that is because comics frequently simplify complex social structures, environments, language, and bodies into single panels, requiring the viewer to extrapolate meaning. As a result, it has been too easy for comics to fall back on exclusionary stereotypes, not least those based on race. The violence of such racialised visualities has only been intensified by the predominantly white (and mainly male) world of comics production and consumption.

Race in Latin American Comics

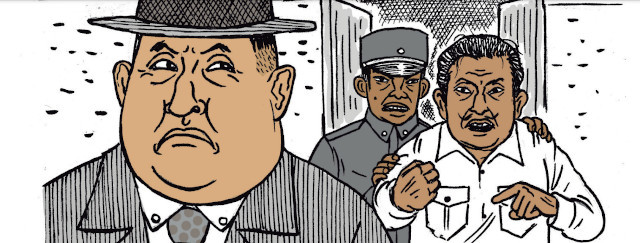

Early Latin American comics (c.1870s-c.1930s), with their close ties to caricature, are invariably offensive in their depictions of racialised difference, reproducing stereotypes relating to animalisms, piccaninnies, and backwardness as a hindrance to progress. But even some comics in this period are complicated by specific domestic racial politics, such as when artists display a certain sympathy towards racial minorities to critique white-mestizo sectors of society. The mid-twentieth century (c.1940s-1970s), a "Golden Age" in Latin American comics production, saw efforts to address exclusionary understandings of race with more diverse and sometimes more complex depictions of racialised others. A new strand of activist comics emerged in this period, engaging with Black and Indigenous histories and subjects as part of an anti-(neo)colonial discourse.

Nevertheless, these more diverse representations frequently depict racialised others as passive victims requiring salvation by figures who embody white-mestizo paternalism. A similar dynamic can be seen in the early neoliberal era (1980s-1990s), which had a devasting impact on comics production. In fact, few comics during this period were particularly concerned with race, with focus turning more to cultures of the underground and urban life. More recently, however, to the backdrop of a renaissance in Latin American comics production, race is a more frequent concern, with comics addressing slavery, the impact of civil conflicts on different racial groups, migration, and intersectional exclusions in relation to gender and sexuality. Nevertheless, despite this growing ‘anti-racist’ corpus of Latin American comics, most works are still created by white-mestizo artists.

Creating anti-racist comics

Seeking out and promoting such anti-racist comics, and working with a racially diverse group of artists was one of our main goals. With that aim in mind, this exhibition is partly the result of a collaboration between a transnational group of researchers and artists who express and identify with different racial, gender, sexual, and class backgrounds and identities, and who speak from different positions of privilege. The artists who produced comics for the exhibition, and those who gave their authorisation to reproduce work already in existence, all come from three Latin American countries: Argentina, Colombia, and Peru. Rather than try and capture comics production across the region, we focus on three countries that offer a window onto some of the main traits of Latin America’s racial diversity in terms of white, Black, Indigenous, and Asian identities.

As a result, the artists have different racial backgrounds and self-identify in different ways, and they take different approaches to comics and use diverse creative styles. But they all share a desire to explore how comics might contribute to more complex understandings of race and to foment anti-racist visual discourse. In that sense, the frequent appearance of their work in this exhibition is part of the process of "drawing back" against the recurring violence of the visual archive, inviting us to think about what ‘anti-racist lines’ in comics might be.

Confronting the racialized archive

One of the biggest difficulties CORALA faced when curating this exhibition, was how to handle racist images drawn from the archive. The violence embedded in such images is diverse, from physical violence enacted upon racialized bodies, to acts of racialized exclusion, extreme othering, or disdainful, patronising, and violent humour. Is it possible to put on display racist imagery without reproducing the violence embedded in those images? What are the pedagogical limits and ethical responsibilities of the researcher when reproducing such images? For this exhibition, we took the decision not to reproduce the images that we found the most offensive. Technological constraints make it impossible to impose filters on images on all platforms: once uploaded images can circulate freely and to many ends. For that reason, the viewer will find many of the images in this exhibition have been blanked out, with only a description and an analytical text. In instances where these images are already readily accessible online, we have included links; in other instances, researchers who would like to view such images can contact us for more information.

Content Warning

This exhibition contains material that some viewers may find offensive and/or distressing. Please read our full statement on the content.

Exhibition structure

The exhibition is organised into four sections. When viewing this exhibition, we hope viewers will learn something about the relationship between comics and race, and about how racist and anti-racist visual discourses have played out in Latin American comics. The views expressed in the texts that accompany the images are those of the individually named authors. We hope that the range of comments expressed will encourage us all to reflect on our diverse positionalities and relational degrees of privilege, one of the foundations, as we see it, of any anti-racist practice.

Concepts

Concepts

Bodies

Bodies

Temporalities

Temporalities

Landscapes

Landscapes