Many places in Latin America highlight the widespread interconnections between land and exclusion based on race. Works in this section deploy the fragments of the comics page – panels, gutters, lines, etc. – to engage with territorial exclusions and exploitations based on racialised territorialities.

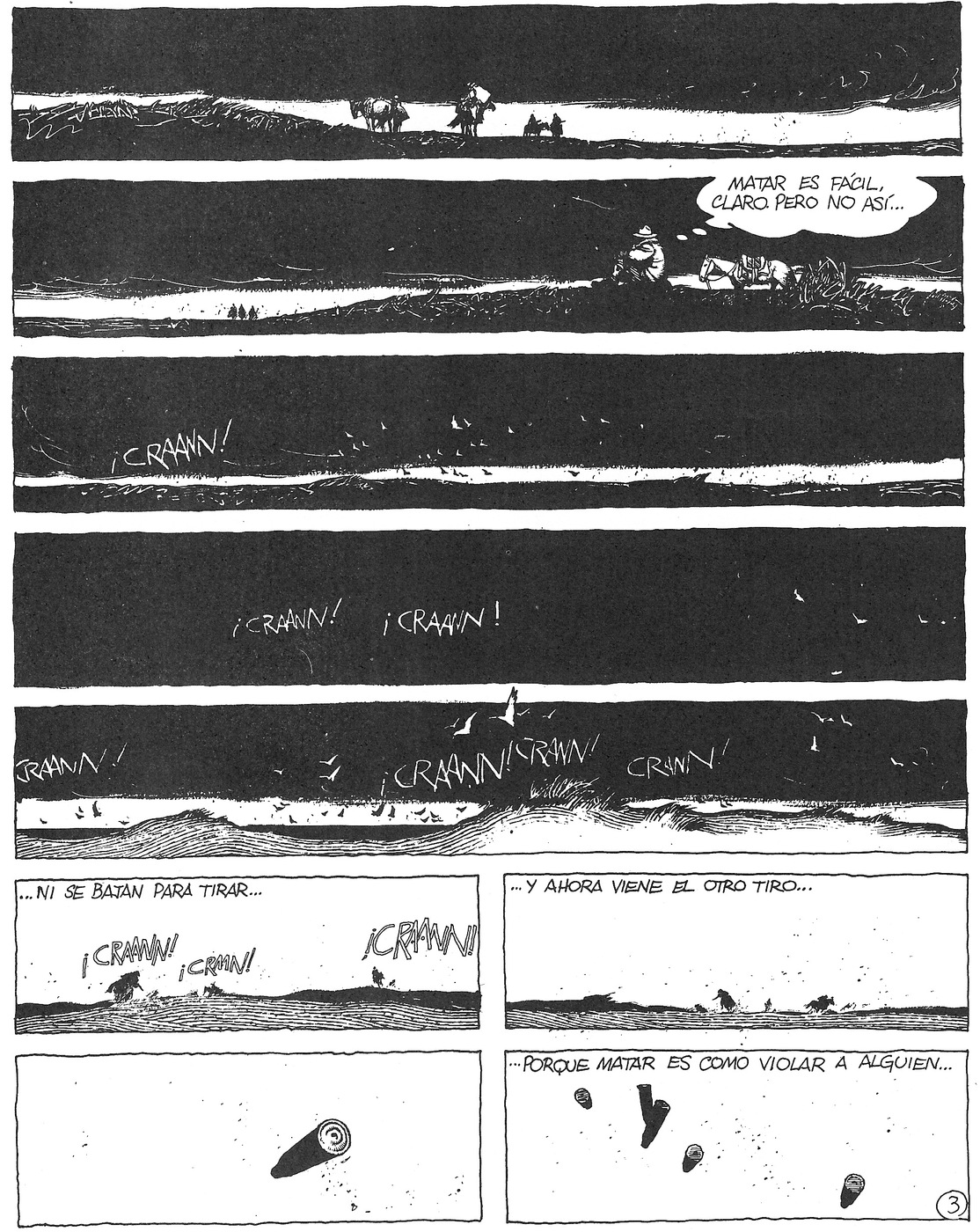

Enrique Breccia’s visual rendering of David Viñas’s 1958 novel, Los dueños de la tierra, was part of Ricardo Piglia’s La Argentina en pedazos, a revisionist series of comics adaptations of canonical Argentine literature published in the magazine Fierro a fierro in the mid-1980s. Though Viñas’s novel is principally concerned with the Patagonian rural labourer strikes that occured in the early 1920s, Breccia chooses an episode that Viñas included near the start of his novel to highlight the links between different oppressed groups: white settlers massacre Indigenous people to try and leave the land "clean, very smooth, ready for working". Though later Breccia includes a frame depicting the mutilated bodies of Indigenous adults and children, here the murders occur beyond the frame, the sound of rifles exploding over the pampas. The panels stretch expansively across the page, as if to highlight the capitalist settlers’ desire to leave the land empty, echoing the euphemistically named "Conquest of the Desert", the nineteenth-century campaign to eradicate Indigenous tribes from lands claimed by the Argentine state.

James Scorer

Domestic service in Latin America is a dense node of social relations at the cross-roads between classism, racism, sexism and ageism - and across the differences between rural and urban life. Most domestic workers are Black, Indigenous or darker-skinned young women from poor rural backgrounds, who work to support their families, trying also to get ahead in life. With luck, their employers allow them time to study, but even so many remain trapped in service or, especially when they have children of their own, move sideways into precarious occupations such as street-food sales. Employers often describe them as “part of the family” as they take on maternal-type roles; children may see “the nanny” more than they see their mother. Yet the domestic workers’ status as powerless subalterns remains the underlying reality and many must endure living conditions much worse than those family members enjoy. Also common is sexual harassment by the family’s men, who often act as if a young non-white female servant from a rural area is automatically sexually available. Michael Guetio’s comic encapsulates these multiple dimensions in a short but rich narrative, making use of the comic’s ability to condense meanings and evoke wider realities.

Peter Wade

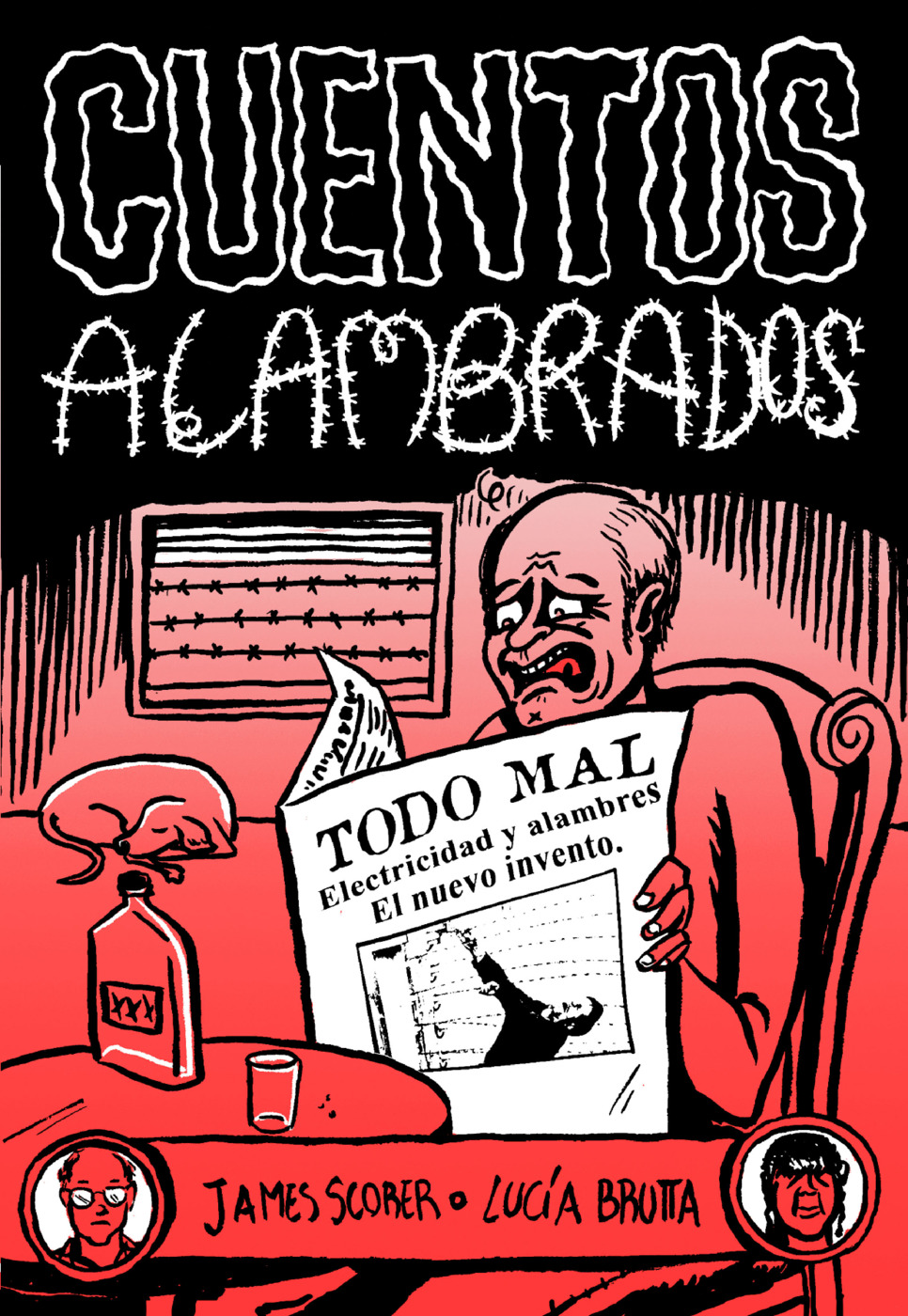

The modern history of Latin America can, in part, be told through the history of barbed wire. In the nineteenth century, Argentine thinker and educator Domingo Faustino Sarmiento celebrated wire as a means of modernising what he perceived as the country’s barbaric and backward rural interior. Wire could turn grasslands inhabited by Indigenous tribes into delimited parcels of territory ready for capitalist expansion. In Peruvian Manuel Scorza’s 1970 novel Redoble por Rancas, wire creeps insidiously across the Andean highlands, highlighting a pernicious extractivism that prevents local inhabitants from working the land. And wire fences run throughout the 2016 Colombian ethno-graphic work Caminos condenados (Ojeda, Guerra, Aguirre, Díaz, 2018), in which the palm industry limits communities’ access to local water sources. In this zine, Lucía Brutta mobilises the multivariate lines of panel edges, gutters, and text boxes, to highlight the multifaceted, transtemporal divisions introduced by barbed wire. But her artwork also captures the bodies tangled up in the racialised extractivisms of Latin America, bodies that all too often remain invisible.

James Scorer

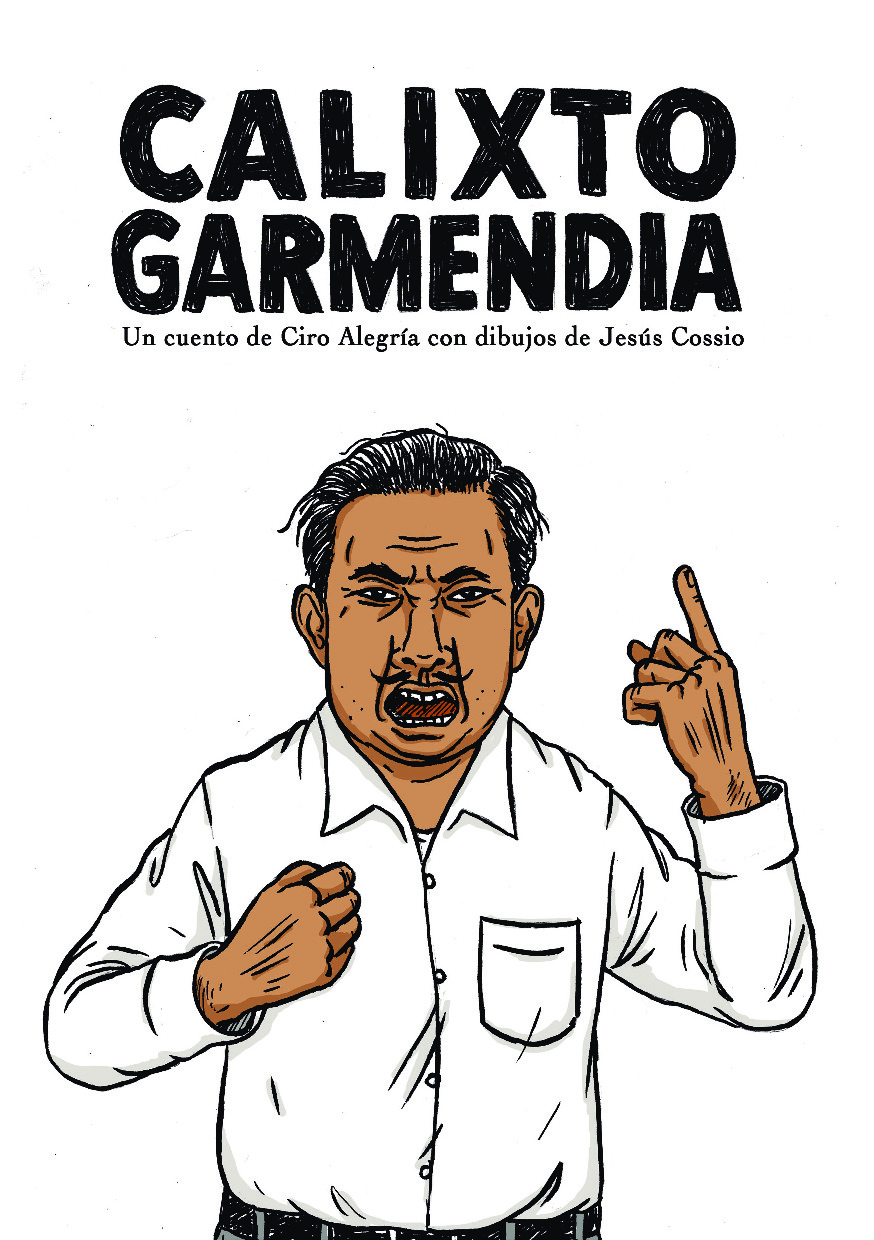

Ciro Alegría’s 1954 story about the carpenter Calixto Garmendia incorporates class struggle, land ownership, social protest, disease, and state indifference. But it is also about racial inequalities in Peru. To visualize Alegría’s story, Jesús Cossio uses vignettes and colour shading to transform a verbally implicit discourse of race into something visually explicit. Cossio narrates racial tensions through portraits and details: the braces, ties, patched ponchos, folded handkerchiefs, knitted hats, and trilbies that the figures wear. The Indigenous agricultural labourers are voiceless without Calixto, the spokesperson who is apparently mestizo, but his illiteracy means his call for "justice" falls on deaf ears: the symbol of his failure is encapsulated in the letters he pays a notary to write on his behalf and to which he receives no response. By reproducing Alegría’s story in a zine, Cossio probes the power of printed words and images to highlight the injustice of transforming land from multi-coloured, thriving vegetable plots into a repository for the decaying remains of the dispossessed.

James Scorer