As well as being related to legal and political territorialities, the land in Latin America is often the basis for cultural identities. Speaking to the territorial exploitations evident in comics in earlier parts of the exhibition, this section shows some ways in which land is connected to such identities – and how comics can showcase such ties.

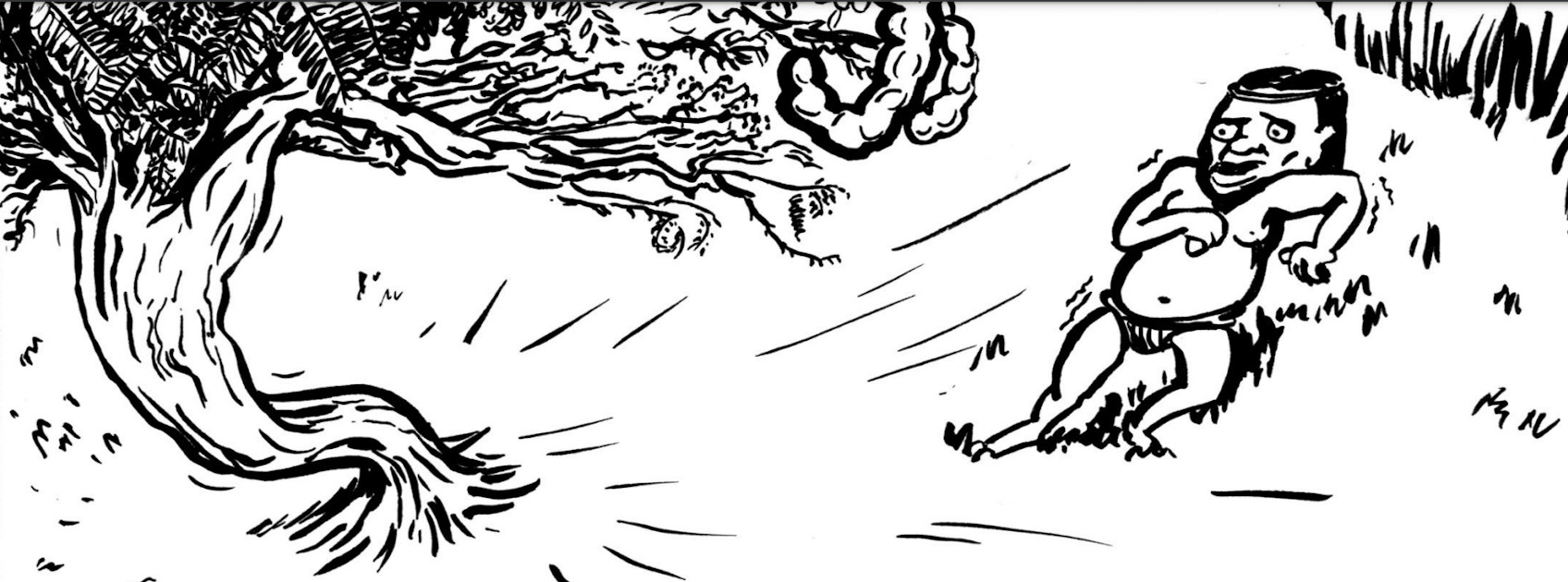

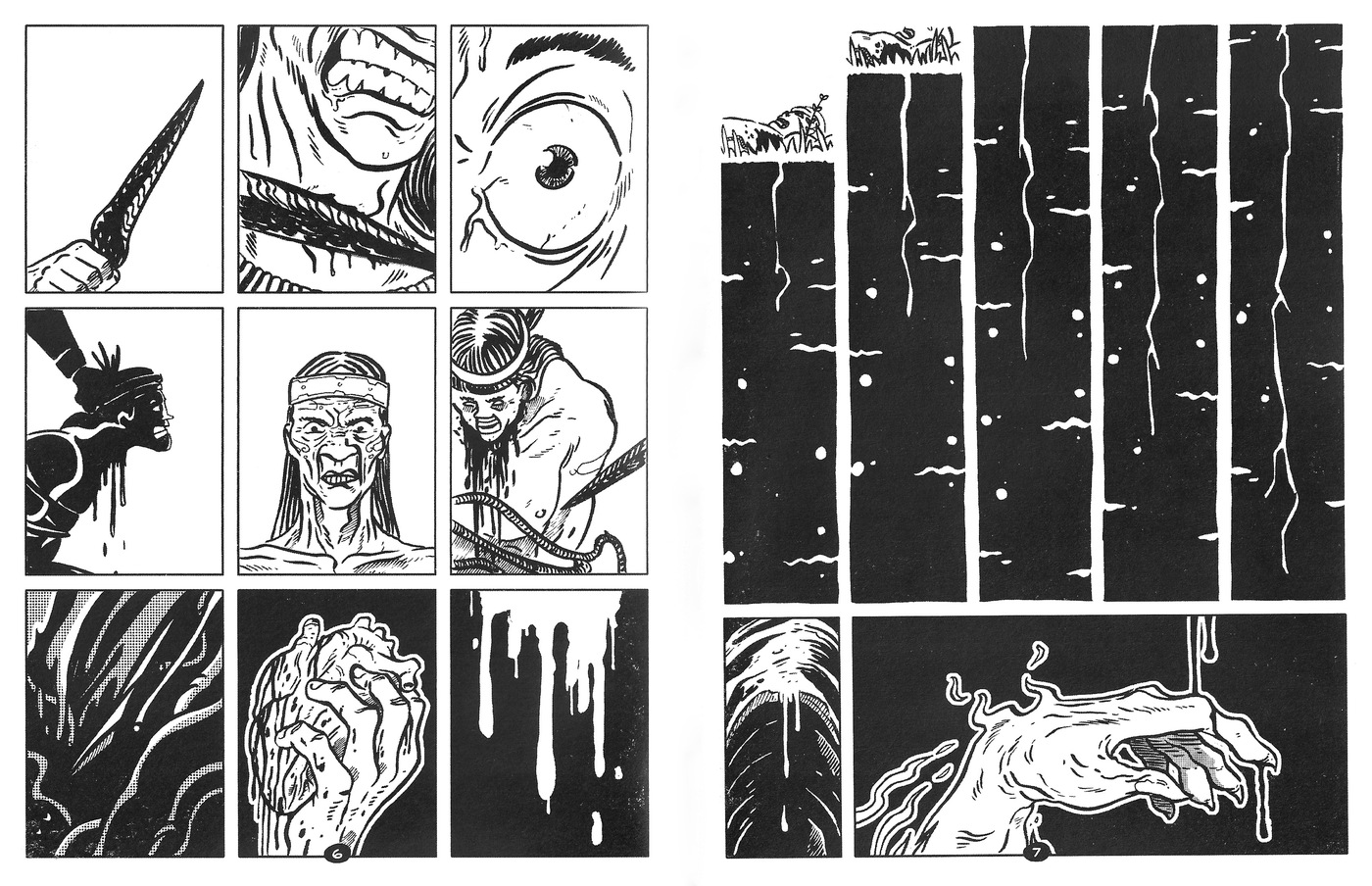

The sixth instalment of El Cerra’o, a fictional horror series created by Julio G. Rodríguez, was inspired by the tragic deaths of construction workers in Cali in 1991. The author notes that ever since, the building, located on the site of a former municipal slaughterhouse, has been haunted. In the comic, the protagonist exorcises a spirit that is plaguing a boy who lives in the building. But by opening with Indigenous blood seeping into the expanding panels of earth, El Cerra’o traces the layers of suffering that underpin a history of capital embedded in the soil.

Rodríguez references the mining industry, the dripping carcasses of animals at the slaughterhouse, and the collapse of a concrete structure in the modern city. But citing the violence of the Conquest and Indigenous suffering, highlights that the slaughtered body is not just ‘a focal point of cruel exploitation and death as a way of reflecting the exploited, expropriated, and alienated body of the labourer’, in the words of Gabriel Giorgi (2014: 135), but also part of a wider racialised dynamic.

James Scorer

This comic narrates Pedrito's journey from the highlands of Puno to Arequipa and Lima. The Indigenous child is depicted wearing a poncho and barefoot, his body portrayed with rigid and hieratic poses, reflecting a subordinate situation in most scenes. The comic's structure unfolds in three pivotal moments: the child's solitude following the loss of his mother, the assistance he receives from adults to navigate the journey to the city, and his eventual decision to leave Peru. Artist Demetrio Peralta (1910-1971) employs an omniscient narrator to underscore the relationship between these Indigenous children and the predominantly white-mestizo adult world. Each panel illustrates Pedrito's subjugation to adult authority, aimed at averting deviation or degradation due to his racial background, following the eugenic policies of the era. He emerges as a passive character, lacking control over his life and subject to physical and verbal violence. Ultimately, the only viable path presented for the child is migration, seen to embrace the values of Western civilization. The comic serves as a reflection of the contradictions inherent in the Peruvian indigenist project. While aspiring to cultural transformation, it perpetuated racial hierarchies, framing these narratives as tales of triumph over adversity, concealing a subtle form of racism.

Malena Bedoya

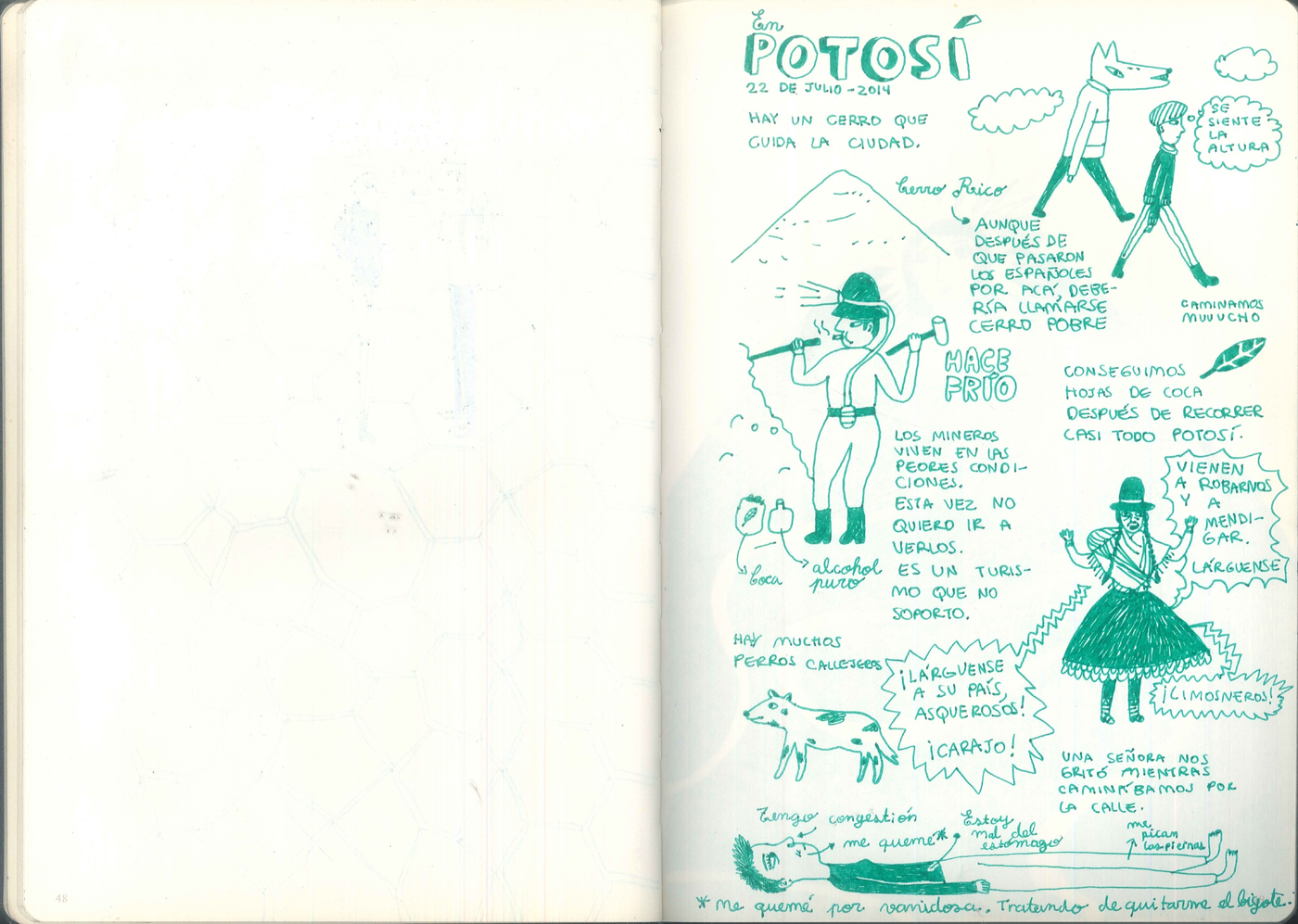

This comic page by Ecuadorian-Colombian comics artist Power Paola represents a page of a travel log describing her own travels with her partner to Potosí, Bolivia, a city with a long history of mining extractivism based on Indigenous and Black exploitation. Narrated in the first-person in a self-referential mode, the page centres her own comics character’s point of view, experiences, and values. A white or white-mestizo (someone who would be identified in Colombia, Bolivia, Ecuador as “blanca”) middle-class tourist, the comic’s main character is preoccupied with minor ailments, insists on getting hold of coca leaves, notes the abundance of street dogs, and, seemingly oblivious to her own racial and class privilege, describes an Indigenous woman who screams at her and her companion in the street without adding any self-reflexive commentary on that respect. The banal is presented in the same tone and narrative level as commentaries on historical and social issues, such as the pauperization of Potosí, trivialising, in this way, white middle-class privilege and overlooking discussions about race and inequality. Whether the deadpan delivery is intended to be descriptive or ironic, and what the implications of that would be, is up to the reader to decide. The comment about not wishing to “go see” the miners “this time around” exemplifies the complexities of travellers either engaging in poverty tourism or turning their back on poverty, often in ways that don’t consider the structural causes of poverty and tourists' own implication in them. All these elements illustrate how white-mestizo privilege (Cerón-Anaya et al 2023) operates and the deployments of the white sight (Mirozeff 2023), the mestizo gaze, (Ortega Domínguez 2022), mestizo innocence (Saldivar Tanaka 2022) and what Jamaican philosopher Charles W. Mills (2007) identified as white ignorance.

* “Los mineros viven en las peores condiciones. Esta vez no quiero ir a verlos. Es un turismo que no soporto”.

Abeyamí Ortega

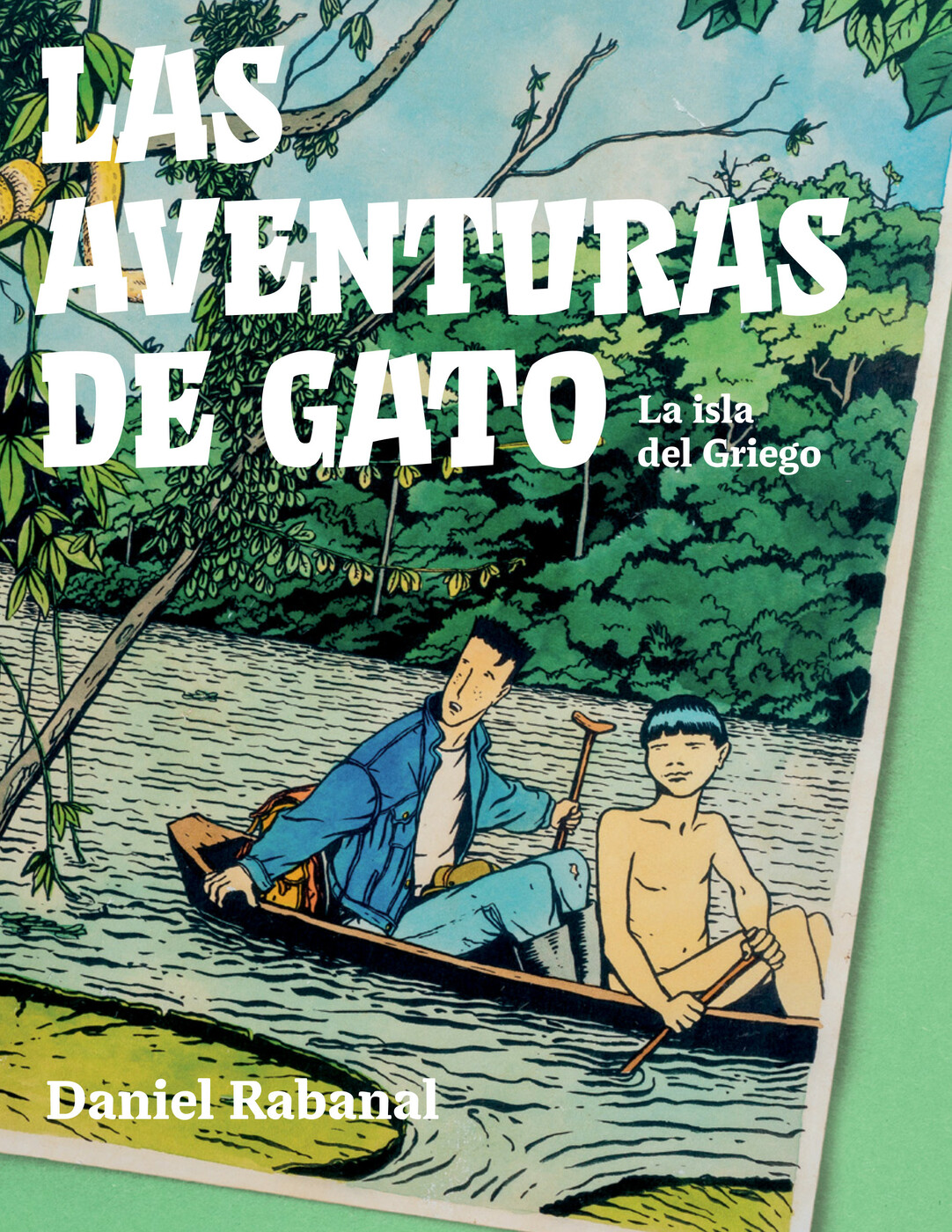

Las aventuras del Gato: La isla del griego is a comic strip created by Argentinean artist Daniel Rabanal. Published between 28 January and 25 August 1996, it appeared in the Sunday supplement Los Monos of El Espectador. Rabanal, who lived in Colombia in the 1990s, presents a different vision through his main characters - El Gato, Kurt, Nagori and Tacuma - in which the defence of nature becomes a shared objective. Their mission: to stop and denounce the illegal trafficking of species led by "El Griego". Tacuma, a young Indigenous boy, clearly identifies the problems in the jungle with the actions of the white man and his unbridled quest for enrichment. In the same vein, the protagonist's commentary expands on this critique, pointing out that these attitudes are not exclusive to the jungle environment, but extend to other spheres, thus underlining the inherent problem of such whiteness in different socio-environmental contexts. Although Rabanal uses a generic term to refer to the Indigenous population he represents, his comic opens a critical window on the environmental crisis and extractivism that affected various Colombian Indigenous communities in the 1990s and continues to the present.

Malena Bedoya

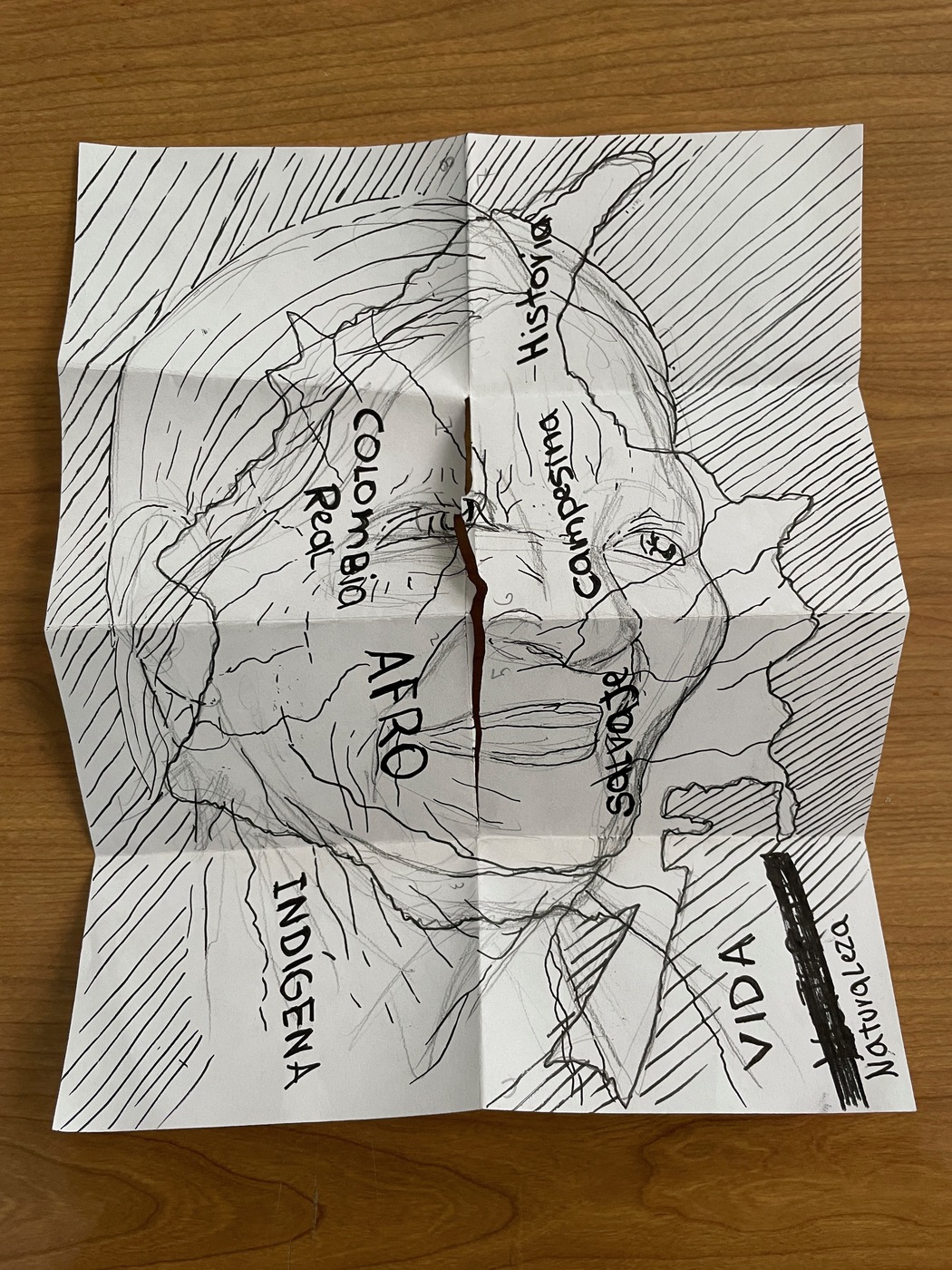

In this zine, created during a workshop organised by CORALA in collaboration with the Banco de la República, Cali, the Indigenous Nasa artist Michael Guetio places the sketched portrait of an Indigenous woman over a map of Colombia. Using a common technique to create a zine – a sheet of A4 folded and partially cut to make a small booklet –, Guetio mobilizes the process of unfolding and turning the zine to create a material process of discovery. Revealed in its entirety, the words that initially confront the reader – Afro, Indigenous, Life, Nature, Savage, Rural Labourer, History – appear as part of the montage Guetio creates: language, body, territory. Here the traces of one Indigenous hand, manifest in the fusion of flowing and striated pen lines that make their way across the page, embed another Indigenous body in the land: the woman’s face shares some of the same lines that demarcate national territory, highlighting the parallel and multiple temporalities and racial identities that comprise the modern Colombian state.

James Scorer

Crónicas de la Resiliencia is a graphic novel that challenges traditional power dynamics and hierarchical structures by highlighting the voices and experiences of historically marginalized communities, particularly Afro-descendants. It reimagines the relationship between humans and nature, emphasizing equality and cooperation with non-human entities like turtles. Drawing on critical posthumanist perspectives, the novel questions the notion of human superiority over nature and critiques racial and gender hierarchies.

While it falls short of fully interrogating the concept of race, the novel's political imagination encourages a re-evaluation of social ecologies and human-nature relations. By centring the narratives of marginalized groups, it disrupts mainstream comics' tendency to prioritize a human-centric perspective. Ultimately, Crónicas de la Resiliencia represents resilience as more than just survival—it's a radical political project that seeks to dismantle racism, sexism, and anthropocentrism. By repositioning marginalized representations, it proposes a vision of a more just and sustainable world for all beings.

Abeyamí Ortega