Knowledge exchange

For centuries, the Chinese exchanged knowledge with other people including Arabs, Persians and Indians. Especially from the late Ming dynasty onwards, they encountered a new group of foreigners, Europeans. Some Europeans were missionaries while others came as armed merchants. Jesuits, members of the Catholic Society of Jesus, were among the first arrivals.

When the Qing came to power, they kept the Jesuits at court for their knowledge of astronomy and science. Trade was crucial too, as traded artefacts revealed information about production techniques. Exports to Europe increased during the Qing era, particularly of highly sought-after Chinese porcelain.

In summer the emperors lived, worked, and entertained in their palaces outside Beijing's city walls. While this complex was constructed by Chinese craftsmen, some elements were designed by Europeans.

In 1747, Emperor Qianlong employed the Italian Jesuit Giuseppe Castiglione as designer of European-style palaces and gardens. The French Jesuit Michel Benoist engineered several fountains. This engraving reveals a fusion of styles and knowledge: Chinese zodiac figures and European fountain technology.

At the end of the Second Opium War, in 1860, British and French troops looted and burnt down the palaces.

European and Chinese astronomers studied the skies and shared their knowledge. These hand-drawn star maps combine East Asian and European understanding by complementing Chinese names with transcriptions in French.

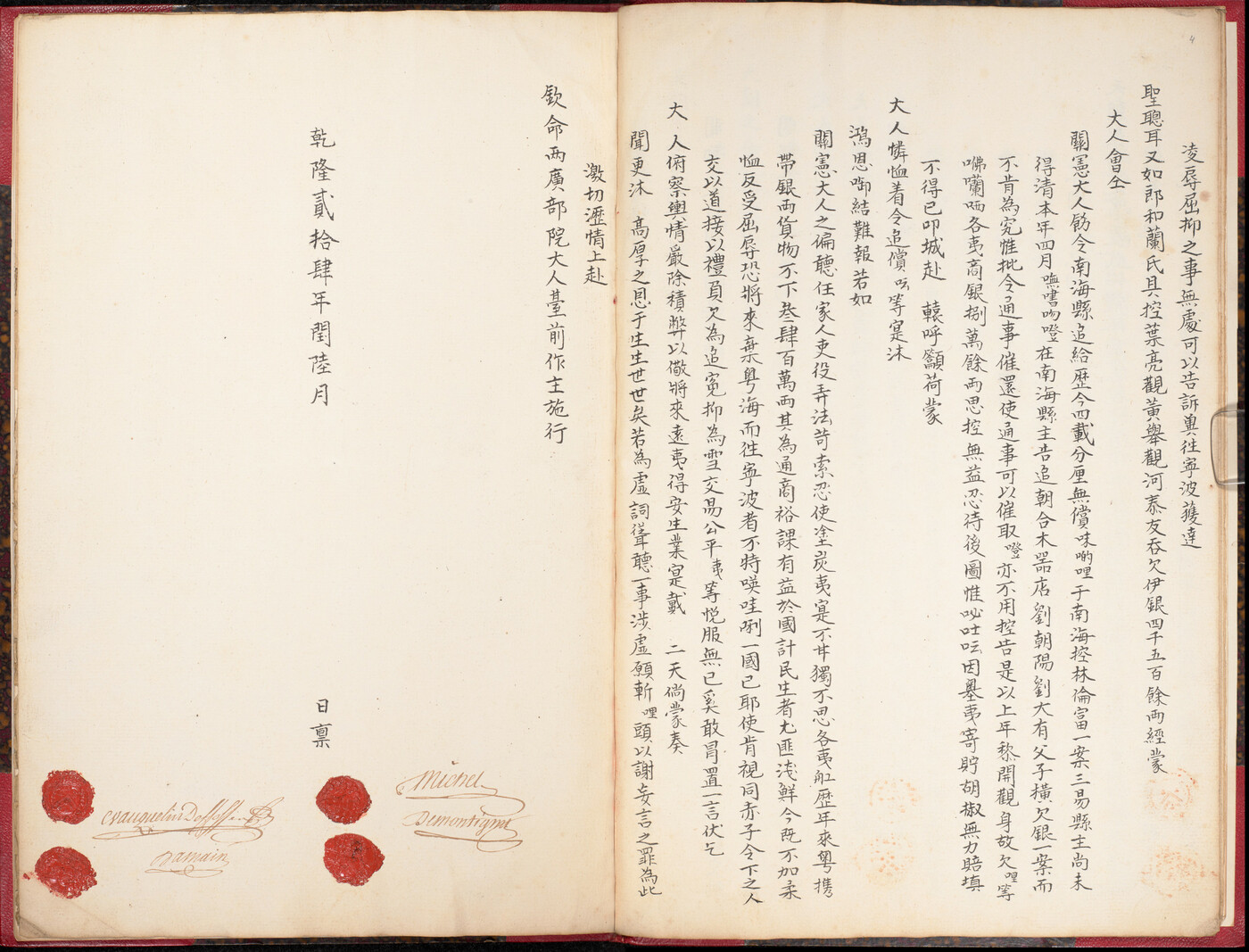

China experienced an intense boost in global trade during Emperor Qianlong’s reign. From 1757, the Qing allowed Europeans to trade through the port of Guangzhou (Canton). In this petition, a European merchant makes several complaints including perceived unhelpfulness of Qing interpreters.